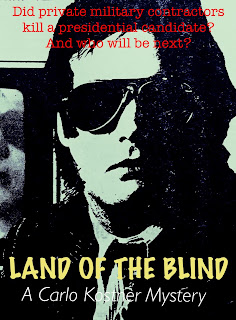

A Carlo Kostner Mystery

: Chapter Two :

THE THING ABOUT being a rescuer is that you tend to see problems as challenges rather than threats. You think, how bad could it be? After all, Rose Broadcasting was a revered institution, a national voice for peace and nonviolence populated with dedicated, sometimes gifted people. It was an honor to have an opportunity to lead, even if it felt a little tentative. The Board was rife with intrigue, and there were queasy rumors about the hiring process.

Now I think: How bad could it get and where can I hide?

Known as The Rose, it had taken the name of its late beloved founder Leonard Rose, and as a reference to what roses often represent – love and beauty. Anyway, it made for an enticing logo.

Yet there was irony in the symbol. Rose is also the national flower of both the US and England. Long before that, early Christians adopted it as the symbol for their martyrs. The association with socialism and the left developed centuries later, linked to the British and Irish Labour parties, not to mention assorted left-wing political groups across Europe during the 20th Century.

In May 1968, it became a badge of honor for street protesters in Paris.

But the name also worked as a handy label for conservatives, for whom it served as more evidence that The Rose was pink, maybe even Red, a dangerous, subversive blot on the media landscape, a network of left-wing stations that “blamed America” for everything wrong in the world and supported disloyal, decadent elements in our society.

Obviously that wasn’t how Leonard Rose had defined the mission, or how loyal Rose watchers saw it. For them it was the voice of truth and justice, a source of hope for a better world.

Officially, it was the Rose Broadcasting System, a worker-managed, listener-supported multi-media company, owner of operations in half a dozen large markets, and frequent site of internecine political warfare. Over the decades it had grown from a single Los Angeles TV station into a network with billions in assets, millions of listeners, and a structure so Byzantine that even ardent defenders considered it dangerously dysfunctional.

Before I became its chief executive, a colleague from the Pine Tree State dubbed it “the dream job from hell.” I found the description amusing at the time. Nor was I dissuaded when one Rose GM explained why he wasn’t interested in the job despite ample qualifications and political connections. “I want to survive,” he said. ”Professionally, and otherwise.”

I followed up. “What the f--k does that mean?”

“It means,” he said, “that people who get there also tend to get bloody. Rumors, media vultures, that kind of thing. It’s tough to find a home afterward.”

He didn’t mention being assassinated or framed for murder. But obviously I should have taken the advice more seriously.

A month later, I was on my way to Rose headquarters in New York, located behind an unmarked door in the same building as WARP, one of the oldest operations. But first, that stopover in Washington, DC to meet with Gene Montoya, American success story and the next big thing.

Most people know the basics about Gene, or you might say, the “approved script.” Starting out the son of a poor Mexican immigrant and an Irish beauty queen, Gene Montoya had managed through hard work and political genius to become mayor, then congressman and most recently governor. At the time of my invitation, he was something even more exciting, a well-funded independent candidate for President. Less widely known was the fact that we were friends at one time, although I hadn’t heard from him since his star began to rise.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I should mention the last time we saw each other, about eight years before our reunion. He was standing in the third floor window of New Mexico’s state capitol, known as The Roundhouse and designed to represent the Zuni symbol for the sun – the only round state capitol in the country – watching dozens of anti-war protesters get dragged away roughly by the police for committing civil disobedience. I don’t know whether Gene personally issued the order, or even noticed me sitting cross-legged on the ground with the rest of an affinity group.

For a while I held it against him anyway.

This was definitely not the same dude I remember from our days with the Magic Coyote commune. Clearly people can change in twenty five years. In any case, about a year ago he asked to meet. Despite the hand-written invite – probably penned by a sycophantic intern – I didn’t believe that the reason was a sudden urge to reminisce about the good old days.

That sun-fried afternoon in Santa Fe, when dozens of us were manhandled for demanding an end to bombing and lies – What else is new? – wasn’t the only time I was arrested for a good cause. About two years later it happened again, this time by accident while I visiting a campsite established to “Save the Rose.” There were earlier encounters with the fuzz, of course. All the Magic Coyote communards, myself and Gene Montoya included, were shackled and booked back in the day. It was the thing to do, a social obligation, a mark of honor.

Saving The Rose had a similar allure. After all, it had been "hijacked" by corporate hacks and “We the People” would do whatever was needed to “take it back.” In other words, by any means necessary. Sartre coined the phrase but Malcolm X made it an article of faith and the Internet turned it into an acronym – BAMN.

I use "we" somewhat loosely, since I wasn’t a member of the inner circle. But I did visit Ground Zero – a scruffy park near the business office on the outskirts of the capitol – just in time to be rounded up by the cops.

The tension had been building up for months, and finally reached a boiling point when armed guards tried to arrest Gail Sahara, not yet the media celebrity she became but already popular as host of “Open Forum.” Then she charged on the air that the Board of Directors was scheming to sell the Los Angeles station. Her arrest was stopped by then CEO Carter Larkin (one of my discredited predecessors), yet Gail joined others on a growing list of the “fired and banned.” Within a week, thousands were committing not-so-civil disobedience outside Larkin’s office.

All this may not seem especially relevant to the untimely demise of Gene Montoya. But it helps to explain the Rose as a born-again democracy, and why I could end up in charge.

The"revolution" that created the “New Rose” began when the Board of Directors, chaired by former Under-Secretary of Education Rebecca Alice Lemon, voted to change the governing structure. There had been internal fights for years, but this time Board members claimed they were being forced to comply with government rules.

The problem, claimed Lemon and her allies, was the Community Involvement Panels that “advised” management at the stations. The Corporation for Public Media had allegedly informed Rose executives that the Board would have to sever official ties with the CIPs to remain eligible for public funding. Even though Rose was financed mainly by listeners and underwriters, an increasing proportion of its revenue was being provided by the Feds. Cutting out the CIPs meant a bylaws amendment that would essentially make the Board self-perpetuating. Whether the CIPs ever had any binding control over the stations – and whether the change was actually what the CPM had in mind – are both fair questions.

The first person to challenge the Board publicly was a producer, Hardy Berman, the professional curmudgeon who urged Gail Sahara to talk about the crisis on her show. Berman, an irascible, astute pro who found a home at the Rose during the sixties, was promptly suspended for violating a so-called "non-disclosure" rule. He later claimed that the trouble began when Larkin refused to renew Capital Bureau Chief Sandra Black’s contract.

Black was a recent hire and popular with staff. Soon after that Larkin issued a statement intended "to clear the air." But his explanation included harsh words for both Berman and Sahara. The feisty host, probably egged on by the Berman, fired back by reading Larkin’s statement on her show, then proceeding to discuss internal network business. This violated a so-called "no dirty laundry" policy.

There was a policy for almost any occasion, yet apparently never the right one.

In her own defense, Sahara said her comments focused on “how concerned I was, as someone who has been with the Rose a long time, about what I considered authoritarian power plays and a wasteful bureaucracy." A few days later Berman was fired for letting her express that opinion. Sahara, an effective fundraiser, was spared but warned to shut up.

In another version of the same story, Berman wanted to be fired in order to become a martyr and light a match under the activist base, and Larkin didn’t renew Black’s contract because she was too friendly with Sahara and Berman, who felt they could control her and thus the network’s political agenda. Still another version had the Rad Couple, as they were known, embezzling funds and writing themselves checks. Larkin never claimed that happened. But he did say an investigation of spending for “Open Forum” was being pursued. This was more than enough to rile the rumor mill.

Anyway, a key moment was Berman’s removal – in handcuffs -- from the DC studio after an altercation with Larkin and the security staff. The story goes that Carolina Cruz – about whom more later– had just been selected to replace Black as head of the Capitol Bureau and asked Berman to come over for an orientation. That much was verified. Beyond this it becomes “she said, he said."

Berman later claimed that Cruz threw her cell phone at him. She charged that Hardy was “belligerent” and "knocked over stuff," then falsely claimed that he had been assaulted. Whatever the truth, Hardy’s supporters were milling around outside the door, heard the ruckus, and were ready to believe him. But their presence also fueled suspicion that a subsequent public shouting match between Berman and Larkin in the hallway, complete with finger poking and enough contact for the alpha males to exchange spittle, may have been staged.

What’s indisputable is this: Larkin called in security and they dragged Berman out of the building.

But that was child’s play compared to what came next, As Sandra Black told the story, she had visited the office that same day to pick up her severance check. Although sensing that someone was following her home, she didn’t respect her intuition. When she stopped at a traffic light, a non-descript car – “like one of those unmarked government vehicles,” she told the police – sped past.

A gunshot smashed through her windshield, missing her by less than a foot.

The police couldn’t find a suspect, so no one was arrested or charged. Within Rose circles, however, the spin was that the attack was a warning – in response to the story being developed by the network, with Black’s support, about phony terrorist scares designed to gin up paranoia and justify just about anything in the name of national security. For some Roseniks, a government plot is the first and easiest explanation for any unexplained (aka suspicious) occurrence.

How this relates to my working for the network has several angles. First of all, I knew the stories and, like other believers in the promise of progressive media, I wanted to help save the Rose.

The Board and management had banned discussion of the crisis on the air. More staff was being fired, and as the protests grew Lemon asked the police to crack down on the demonstrators. With wartime logic in effect, the feds and cops had the tools and were ready to punch. But persistent protests forced the police to investigate the attempted shooting of Sandra Black.

Over the next weeks, Lemon accused the opposition of violence and racism, the staff union filed unfair labor practices charges, federal mediation was launched, and a cadre of listeners filed a lawsuit demanding repeal of the “self-perpetuation” amendment and removal of the entire Board. Just when everyone thought the tension couldn’t get any worse, a confidential e-mail was circulated. It revealed a secret plan to sell off stations, a charge Sahara had leveled on the air before being threatened with arrest and banishment.

By then I was on a cross-country road trip to the protest site, which had become a semi-permanent encampment surrounded by riot police and renamed Roseland. Less than two days after I arrived, cops invaded in the dead of night and made hundreds of arrests. I spent hours in a DC holding cell. But the next day Roseland was back in action.

For me it served as a baptism. You might say I was born again as a part of Rose Nation. From that point on, I felt that I had a direct stake in the outcome of this revolution.

It was also an effective, especially apropos distraction from grief, since that same weekend was the last time I saw Renny, the love of my life and the bane of my existence. After a bizarre courtship – she was considered an enemy of the state when we first met – we had lived and traveled together, driven each other nuts, and broken up on two continents.

I am not over her yet.

Second, I began to investigate questionable “terrorist” incidents, particularly the possibility that some of them might be hoaxes, and that line of inquiry led to “Outsourcing War,” which put our small production company on the map. The movie, which won some festival prizes, reached art houses, and was ultimately sold to Netflix. It exposed and tracked the creeping privatization of war, which has proceeded for decades but escalated sharply in recent times.

Finally, and perhaps most crucially, I became General Manager and CEO largely because some people never forgave the other leading candidate for her ambiguous role in the network struggle. Carolina Cruz had survived the Rose Revolution – not surprising for someone who overcame an abusive father and death squads in Central America. She remained a muscular gatekeeper in the network. But neither her connections nor award-winning productions were enough to counter the charge that she was a power-hungry predator who could not be trusted.

As insiders often said, “Welcome to Roseland. Feel the love.”

Next Chapter

Previous Chapter