Progressive Eclipse - Chapter Eight

UPON LEAVING THE mayor’s office after four terms, Bernie Sanders donated more than 50 boxes of official papers and files to the University of Vermont library. The index created by UVM's Special Collections listed around 1,400 separate files covering March 1981 to November 1988. According to Sanders aide George Thabault, much correspondence during the first few years had been lost. But what remained ran from Abenaki to Zoning. About 10 boxes covered areas like administrative meetings, speeches and statements, commissions, selected departments and people, proclamations and controversial topics.

To a supporter who thought, in 1988, that Sanders was a socialist candidate for Congress, he explained candidly, “Socialist is the political and economic philosophy I hold, not a party I run under.” And when two Californians asked in a letter, “What does Socialism really mean in the United States at the current state of conditions and confusion that exists at all levels?” he offered this characteristic reply:

|

| Reading poetry at Maverick Bookstore, 1986 |

“That’s an excellent question which I really don’t have time to answer now. I will simply say that in Burlington we have a three-party system – Progressive, Republicans and Democrats, and that I think we are doing many good things for working people, poor people and elderly people in our community.”

People often urged him to run for one thing or another. They also offered advice, warnings and pats on the back. Author Gerard Colby, for example, noted in a November 1983 letter that interstate banking would hurt efforts to stop condominium development on the waterfront by giving entrepreneurs and developers “a valuable and powerful ally beyond Vermont’s borders.” Three years later, that became a hot statewide issue.

Around the same time, Montpelier attorney Richard Rubin expressed his concern that the city might be duped in dealings with developers of the waterfront. “I thought I would point out to you that the term ‘profit’ has little meaning in large-scale real estate developments,” he wrote. “These projects can operate as substantial balance-sheet losses but still be quite lucrative to the investors. I am sure there are good accountants who can explain this to you.”

By Spring 1984, Sanders had statewide visibility and growing political power. With George Thabault’s victory in solidly Democratic Ward 5, the Progressives had gained a sixth seat on the City Council. Sanders considered briefly, but then rejected the idea of a run for governor that year. Many people offered opinions on what he should do. Among them was Democrat Peter Welch, himself a potential statewide candidate. Welch wrote, “Congratulations on your recent victories. Perhaps your opponents have come to the reluctant conclusion that the politics of obstruction doesn’t work. While I understand your decision, many have looked forward to your campaign. Perhaps another day.”

In 1990, Sanders did the convincing. He persuaded Welch to run for governor instead of the US House of Representatives, while he made his successful bid for Congress. Welch lost. But the two remained political allies, and when Sanders became a US Senator in 2006 Welch replaced him in the House.

Occasionally Sanders offered advice to presidents. To Ronald Reagan, on the occasion of declaring October 24-31, 1981 Disarmament Week in Burlington, he wrote:

“I urge you, in the strongest possible way, to stop doing ‘business as usual.’ International conflicts can no longer be solved by war. It has no worked in the past, and it may well destroy the world in the future.”

Several years later, he made a proposal to former President Carter: that Carter visit Nicaragua and help build some housing. “Your presence there,” he urged in August 1985, “would send a powerful message to the citizens of the United States, challenging them by the model of your own efforts to provide material aid to help the people of Nicaragua in constructive ways."

Despite his stated desire to change military and foreign policies, however, there wasn’t much in his papers about local support for these goals. His coolness to economic conversion of Burlington’s armaments plant was evidenced by the absence of any file on the subject. In 1987, he did note to activist Robin Lloyd that opposition to any peace initiatives that "cost jobs" would be enormous.

Still, he did add, “I believe that a rational conversion policy will not only result in more employment opportunities for Americans but in a radical improvement in the quality of life in our country.” It was more support for changing basic military spending priorities than he ever gave in public.

On the Rise

By 1983 the Sanders administration and local progressive movement were in high gear. The minutes of the April 6 administrative meeting show a broad and systematic approach. Personnel Director Peter Clavelle and Treasurer Jonathan Leopold were at the center of things. Clavelle ended up succeeding Sanders as mayor. Leopold, although leaving city government after a succession rivalry with Clavelle, returned as the City’s Chief Financial and Operating Officer under Clavelle’s successor Bob Kiss. In 1983, they were pushing plans to expand health insurance for city employees, streamline Council meetings, bring more women into the Police Department, and push through interim zoning.

An April memo listed more than 40 actual and proposed projects, including a rental housing clearinghouse, alternative school, emergency shelter, office of arts and culture, international work camp, taxi subsidies, park improvements, youth center and self-defense classes. Each month the list got longer.

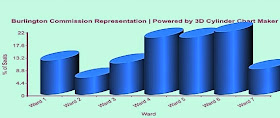

Among Sanders’ frustrations about Burlington’s form of government, commissions were at the top of the list. Commissioners, a majority of them aligned with the Democrats and Republicans, controlled most city departments. Attempts to unify and streamline were resisted until Clavelle, a decade later, succeeded in pushing through charter revisions favoring a strong chief executive. Prior to Sanders’ election the vast majority of commission appointments were made with only one candidate in the running. In 1980, only two out of 25 appointments were contested. Two years later, all but two involved competition.

In a March 1983 letter to the City Council Sanders focuses on one area of concern. “Of the 103 citizens currently serving on Burlington’s commissions,” he reminded them, “only 21 are women. Clearly, the City of Burlington wants to address this serious inequality of representation.” But he wanted more than that, changes in the city charter and shorter terms for commissioners. The current structure, he said, relies on Council members “for handling many routine administrative matters more properly the responsibility of an executive. The Mayor competes with a variety of independent boards, commissioners, committees, and individuals.”

|

| Representation on commissions remains a problem |

When the Council asked for a clarification, the city attorney wrote back, “Some commissions are subject to orders issued by the City Council while other are not.” In fact, at least eight commissions, including traffic, police, planning, parks and recreation, light and the library, were not subject to the council’s orders in areas delegated to them by the charter. Determined to unify administration, Sanders and his staff turned to departmental mergers, starting with the Department of Public Works. Others were considered during the 1980s.

Although leaning toward the fan mail variety, correspondence files were not short on criticisms. One example came from Antonio Pomerleau, the influential developer who had been excoriated by Sanders during his initial run for mayor, yet remained the key man on the Police Commission. In 1987, he finally resigned, confident that he and the mayor had come to an understanding. But less than a year later he was upset to learn that the police force wouldn’t get five more men.

“Remember Bernie at your last re-election,” he wrote heatedly, “you promised the people of Burlington you would put on an additional 20 officers over the next four years…Bernie, this was an absolute definite commitment to the people of Burlington. Let’s get together on this as I am extremely disappointed.”

But was he actually surprised? Hadn’t he heard, from Sanders’ most bitter opponents, that the “Sanderistas” couldn’t be trusted? Perhaps he had missed the Paul Revere-like warning issued several years earlier by state Senator Tom Crowley. Writing to Rutland Mayor John Daley in 1982, Crowley offered a bizarre conspiracy theory.

Daley apparently harbored hopes that, if Burlington’s Southern Connector project was terminated, some of the funds might be freed up for a road in his area. Not likely, responded Crowley. But he went much farther. “Watch this group from Burlington,” he warned. “They are the exact same group that ‘sprouted the seed’ which is flourishing in Burlington now. They started under the guise of the connector as a front. Their program worked so well in Burlington that they have apparently targeted Rutland as Bernie Sandersville number 2.”

Despite such dire warnings, Pomerleau and Sanders did ultimately declare a truce and develop an alliance. Decades later, Pomerleau provided crucial help to Jane Sanders, then President of Burlington College, when the school purchased 33 acres of land owned by the Catholic diocese, even providing a loan of $500,000 to close the deal.

By 1988, midway through his fourth mayoral term, Sanders clearly had his eye on Congress. “While it is true,” he wrote to a supporter in Newport, “that a Congressman is only one of 435, a strong Congressman saying things that few others have the courage to say could have a national impact. Ultimately, the most important questions facing the nation are being dealt with in Washington. It would be very interesting being there.”

Management of day-to-day affairs was now in the hands of Clavelle and Leopold, but the broad vision emanated from his office. When the University Health Center decided to restructure its board of directors, for instance, he was quick to suggest that UHC, the most powerful association of doctors in the state, put a consumer representative on the board. Or, when word filtered back about a conflict between the Public Works Department and city workers, he warned the commission supervising the department that he would “not tolerate any department in this city attempting to subvert the legal contract that we have with the union.”

Sanders’ papers also reveal concern about how his marriage to Jane Driscoll, who had become Sanders’ second wife, would affect her employment as director of the city’s youth office. She had created the office and her job in 1981, beginning as a volunteer, and developed it into a well-paid contract position. William Aswad, a longtime opponent of the mayor who had become a member of the City Council, made not-so-subtle inquiries about her salary and status.

|

| Power Couple: Jane and Bernie with Lance Armstrong |

In May 1988, Sanders asked City Attorney Joe McNeil if the city’s “anti-nepotism” rules would preclude his new wife from continuing her work. The answer was a clear no. Personnel regulations were intended to limit the hiring of a relative, not to prevent existing employees from becoming relatives or forcing them to lose their jobs if they did so. “In conclusion, this office wishes you and Jane a very happy marriage,” wrote McNeil. “This is the first time in nearly 20 years as City Attorney that I have been able to close a legal opinion in this fashion.”

Like watching his administration, reviewing Sanders papers revealed a few blind spots. Environmental matters, local control, participatory management and alternatives in areas like development rarely received more than lip service. Researchers will have trouble finding any Sanders thoughts during this period on nuclear power, growth or pollution. On the other hand, his eight years in local office represented an ambitious attempt to change the rules and scope of local government. Just holding the reins of an unruly, often resistant power structure often took all the effort he and the Progressives could muster.

Maybe the strain was on his mind when he issued one of his more personal comments on the radio.

“It’s all so confusing,” he told listeners one summer day. “And then – life goes on back at home – in the real world. Another farm disappears. Another parking lot is built.” Family breadwinners are afraid to speak out on the job for fear of being fired, he lamented. They have phone and electric bills to pay and car repairs to think about. “And it’s summer time, and maybe we’ll get to the beach, if the lake’s not polluted."

“I’m Bernie Sanders,” he finished. “It’s been a very long day at the office. Thanks for listening.”

NEXT: The Pragmatic Populist

Really enjoyed this. Thank you.

ReplyDelete