The Chicago martyrs became a symbol for workers around the world. Their trial and the hangings made clear the fragility of democracy. In 1886, business and government united to crush ideas they considered dangerous. The bomb provided an excuse.

In 1986, one hundred years after the riot and trial, activists and members of the Burlington City Council gathered for readings and music at my bookstore. In 2003, I partnered with Toward Freedom and Catalyst Theater to produce a play at City Hall based on the events.

These days May Day is fading away again. In many places the date passes unnoticed, even though the issues and political dynamics remain highly relevant. But not in Vermont, where the AFLCIO took the lead this year in organizing a rally at 6 p.m. in Burlington’s Battery Park. For more, go to vt.aflcio.org/mayday.

The words and actions of the Haymarket socialists and anarchists, their sham trial and executions, point to enduring questions about crime and punishment, equality and inequality, class and nationality, free speech and public safety

In 1988, while living in Munich, a magazine asked me for an essay on Haymarket that stressed the connections between Germany and Chicago. At the time I was just starting to work on a script that would eventually become the play, Inquisitions (and Other Un-American Activities). Here’s how I sketched it out to West Germans back then.

Chicago was once the most radical city in the United States. By 1886, its rapid industrialization, fueled largely by massive immigration, had created a polarized environment in which the demands of business owners and needs of workers often clashed.

The working class in this emerging center for commerce and industry was diverse but divided. Skill, occupation, language and cultural differences created barriers to unity, despite the inadequate working and living conditions most of them shared. The labor movement was nevertheless expanding its influence in campaigns to reduce work hours, in the formation of workers’ parties, and the growth of trade unions.

Much of the city’s economic development was based on incredible population growth. Irish, Scandinavian, Czech, English and German immigrants dominated the blue-collar workforce. First and second generation Germans, in particular, comprised 33 percent of the city’s total population. They had their own newspapers, including the Arbeiter-Zeitung, Chicago’s largest radical paper. Their leaders were among the most articulate spokesmen for change.

The bourgeois pressed called these discontented men and women Communists and Socialists, largely unaware of what the words meant. By the 1880s, Anarchist had been added, an attempt to brand labor activists as enemies of all law. But many workers accepted the label, even embracing it as a badge of honor. For them anarchism meant “liberty, equality, fraternity.” They envisioned a free society based on the cooperative organization of production. Essentially socialists at heart, they had gradually evolved into social revolutionaries, coming to the conclusion that peaceful change faced violent resistance from the propertied class.

Chicago’s workers had vivid evidence to support this view. Strikes and peaceful demonstrations were routinely disrupted by heavily-armed police, who beat and sometimes killed unarmed people. Newspapers called for brutal repression. Business created and used private armies to break up labor actions.

Confronted with force, some leaders advised workers to arm themselves, and even to consider dynamite a means of self-defense. “One man armed with a dynamite bomb is equal to one regiment of militia, when it is used at the right time and place,” trumpeted The Alarm, a radical newspaper edited by Albert Parsons.

Parsons was one of the few native-born Americans who led Chicago’s workers. A charismatic and effective speaker, he talked often of a coming social revolution and the need to be prepared (and armed) for it. Though skeptical about the prospects for peaceful reform, he helped to lead the campaign for an eight-hour workday, labor’s central demand at the time.

On May 1, 1886, more than 300,000 workers laid down their tools across North America, united in their call for eight hours. In Chicago, 40,000 went out on strike. Parsons and his wife, Lucy, led 80,000 workers up Michigan Avenue, while on rooftops police and civilians crouched behind rifles, ready to fire on command.

Violence was avoided on this, the first May Day. The Haymarket tragedy was still a few nights away.

Call to Arms

On the afternoon of May 3, August Spies, editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, went to Chicago’s South Side. He had been invited there to address striking workers of the Lumber Shovers’ union. It was Monday, but the empty streets and silent factories made it look like Sunday.

Nearby, other strikers were standing angrily in front of the plant gates at the McCormick Reaper Works. They had been out of work for three months. Confrontations with the police and McCormick’s hired guards were growing more violent each day.

Like Albert Parsons, Spies was an effective speaker for radical action. Born in Landeck, Germany, he had emigrated to the US in 1872, eventually starting a small furniture company with relatives. His main occupations, however, were editing the newspaper and organizing the working class. Fluent in both English and Germany, the 31-year-old editor combined insightful criticism with biting sarcasm. Along with Parsons, he was also a leader of the International Working People’s Association (IWPA), a growing and largely German federation of labor groups.

That day he spoke about the eight hour movement. Before he could finish, however, he was interrupted by violence at the McCormick plant. Picketers had begun to heckle strikebreakers. Police wagons rolled in, and officers entered the fray, swinging their clubs. Showered with stones, policemen drew their revolvers and started to fire. Two workers were killed; many more were injured.

Spies rushed back to his office and composed a fiery leaflet in German and English. “If you are men,” he wrote, “you will rise in your might, Hercules, and destroy the hideous monster that seeks to destroy you. To arms, we call you, to arms!”

An overzealous typesetter, reading the text, added a headline:

REVENGE

Over 2,000 copies of what became known as the “Revenge Circular” were distributed across the city that night. By the next morning, May 4, a mass meeting had been planned to protest the murders. The organizers, among them Adolph Fischer and George Engel, two members of the ultra-radical “autonomist” faction, expected to draw 20,000 people that night to Haymarket Square.

By 8 p.m. only 3,000 people had shown up. Spies was the only speaker in sight. He addressed the crowd reluctantly and urged restraint. Meanwhile, he sent a friend to find Parsons at another meeting nearby. Observing in the crowd, Chicago Mayor Harrison considered the proceedings calm and orderly so far.

Parsons arrived and spoke for an hour, repeating Spies’ words of caution. “This is not a conflict between individuals,” he noted, “but for a change of system, and socialism is designed to remove the causes which produce the pauper and the millionaire, but does not aim at the life of the individual.”

Finishing up, he turned the speaker’s wagon over to Samuel Fielden, an English-born stone hauler well-known for his passionate, earthy style. As Fielden spoke, the night turned windy and a dark rain cloud rolled in. The audience dwindled to about 300 men, women and children. A few minutes more and it would have been over.

But Police Inspector John Bonfield had something else in mind. He was waiting a block away with almost 200 officers. Bonfield was always eager for an excuse to break up a protest. Informed that Fielden was making angry remarks, he saw his chance and ordered his men to march into the crowd. Confronted with armed force, the demonstrators were ordered to “immediately and peaceably disperse.”

“But we are peaceable,” Fielden objected. Then agreed to end the event.

As he stepped down from the wagon, a bomb was tossed into the midst of the police. Its explosion shook the street. Police fired wildly as the crowd scattered. Before the shooting stopped, dozens were injured or dead, among them eight policemen who died of bomb and gunshot wounds. Most of the cops were shot by other officers.

The identity of the bomb thrower was never confirmed, but the establishment and an hysterical press clamored for retribution. Life in Chicago, as well as America’s labor movement and the image of anarchists, were about to undergo a dramatic and long-lasting change. The Haymarket riot engraved the image of anarchists as wild-eyed, foreign-born, bomb-throwing maniacs, a stereotype embedded in popular consciousness to this day.

|

| From left: Louis Lingg, Adolph Fischer, Michael Schwab, Oscar Neebe and Sam Fielden |

The Eight Martyrs

After the bombing, a reign of terror spread across Chicago and far beyond. Public anxiety ran deep. Offices, meeting halls and private homes were invaded. The Arbeiter-Zeitung and The Alarm were shut down as the business community’s newspapers screamed in headlines about Bloody Brutes, Red Ruffians, and Dynamarchists.

Over the next weeks dozens of people were arrested, interrogated and beaten while in custody. The press and legal system agreed, as one judge put it, that “anarchism should be suppressed.” Among those arrested were Spies and Fielden, who spoke that night; George Engel and Adolph Fischer, two organizers of the event; Michael Schwab, Spies’ co-editor at the newspaper; Oscar Neebe, an outstanding organizer and leader of the IWPA; and Louis Lingg, a young anarchist who had arrived in the US only ten months before. Parson escaped but returned as the trial began. These eight were selected to satisfy the public thirst for revenge.

Of the eight defendants, six were German. The oldest, Engel, was 50. Born in Cassel, he had become a socialist after settling in Chicago in 1874 with his wife and daughter. Unsatisfied with the “moderate” views of Spies and Parsons, he joined the “autonomist” faction of the city’s radical community, and, with Fischer, founded the German magazine, Der Anarchist. He hadn’t even attended the Haymarket meeting.

His political comrade, Fischer, was 27, also married with three children. Growing up in Bremen, he had emigrated in 1873 and reached Chicago nine years later. A nervous, individualistic type, he worked in the Arbeiter-Zeitung office as a typesetter.

Michael Schwab, 32, was a Bavarian who had reached Chicago in 1879. Married with two children, he was a mild intellectual man who had turned to socialism after witnessing the evils of capitalism in Europe. At the time of the bombing he was speaking at another demonstration across town.

Oscar Neebe was born in New York, but his German parents had returned to Hesse-Cassel when he was quite young. He returned to the US as a teenager, eventually marrying and settling in Chicago in 1877. He ran a small yeast company with his brothers and was active in the labor movement in his spare time. Along with Spies and Parsons he was a leader of the IWPA. He knew nothing about the bomb until the morning of his arrest.

Louis Lingg, born near Mannheim, had become an anarchist after meeting August Reinsdorf, who was beheaded in 1885 for plotting against the Kaiser. An outspoken believer in “rude force to combat the ruder force of the police,” Lingg quickly moved into the armed section of his Chicago union after reaching the city in 1885 at the age of 21. Though he spoke little English, his good looks and strong views made him a popular figure. Of all those ultimately charged with responsibility for the Haymarket tragedy, Lingg was the only one who had actually manufactured bombs. That said, the bomb detonated that night wasn’t one of his.

These eight, with little more in common than their commitment to radical change, became the targets of official and ruling class revenge. Although only a few were present at the event and none could be directly linked to the bomb, they were charged with murder. But clearly their views, not their actions, were facing judgment. Prosecutor Julius Grinnell made this explicit when he stated at the trial, “Law is on trial…Anarchy is on trial.”

The defendants understood the situation and had little faith that justice would prevail. However, they didn’t expect that all but one of them would be sentenced to death. Even these radicals had underestimated the paranoia and vindictiveness of a fearful public.

|

| Listen to Inquisitions “ …inarguably timely now, as the contradictory demands of national security and civil liberties are once more at odds.” - Seven Days, VT |

Verdict and Legacy

The Haymarket trial was one of the most shameful moments in American judicial history. From the beginning, selection of jury members who openly admitted their prejudice, there was little doubt that the defendants would be convicted. Throughout the proceedings, Judge Joseph Gary was consistently hostile to the accused. In his instructions to the jury, he sealed their fate by saying that, if the defendants had ever suggested violence, they were guilty of murder — even if the actual perpetrator could not be found.

After the verdict, death by hanging for all but Oscar Neebe, the defendants spoke to the court. Most of them noted that the state was betraying the ideals on which the US was based. Spies said that they were condemned “because they had not lost their faith in the ultimate victory of liberty and justice.”

Parsons pointed to the use of violence, including dynamite, recommended by newspapers as a solution to labor troubles. And Lingg, ever defiant, told the court, “I despise your order; your laws, your force-propped authority, hang me for it.”

A strong campaign to save the condemned was launched. Many people who did not share the ideology of the anarchists nonetheless knew that the verdict and death sentences were unjust. Though an appeal to the US Supreme Court failed, public opinion began to shift. Labor groups, at first hesitant to support the men, joined the petitioners asking Governor Oglesby to intervene. Authors such as William Dean Howells and journalist Henry Demarest Lloyd joined with Europeans in pleas for justice. At one point, the governor considered clemency, but powerful businessmen spoke against it.

Meanwhile, the defendants reconciled themselves to their fate. Parsons, who had surrendered himself for trial after evading capture for six weeks, continued to write from his prison cell. He rejected the chance to obtain mercy by sending a letter of repentance to the governor. Like most of the others, he defended his innocence and refused to beg.

August Spies was married while imprisoned to a young woman who has fallen in love with him during the trial. Oscar Neebe’s wife died, even though he was to be spared. Eventually, Schwab, Fielden and Spies agreed to sign a letter asking for mercy. But later Spies reversed himself again, and urged the governor to hang him and spare the rest.

On November 10, just one day before the scheduled executions, the governor was finally persuaded to act. He commuted the sentences of Fielden and Schwab to life in prison. The rest would be hung the next day.

All but Louis Lingg. On the same day Lingg committed suicide in his cell, using dynamite smuggled in by a friend.

On November 11, 1887, Parsons, Spies, Engel and Fischer faced the gallows. With nooses around their necks, they spoke to the world.

“Hurray for Anarchy,” said Fischer. “This is the happiest moment of my life.”

From inside his hood, Spies shouted, “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.”

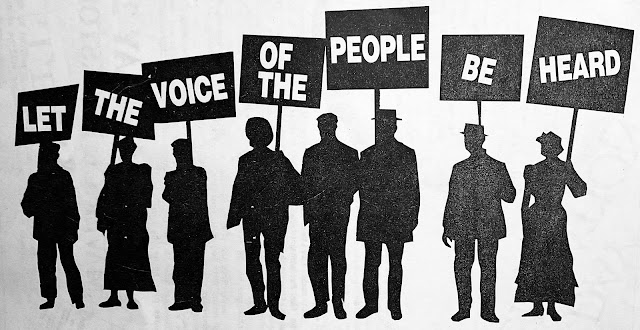

And finally Parsons. “Will I be allowed to speak, O men of America? Let me speak, Sheriff Matson! Let the voice of the people be heard. O —“ The sentence was never finished.

It was not until almost six years later that the truth began to emerge. Another governor, John Peter Altgeld, reviewed the evidence and trial transcripts for months before concluding that a gross injustice had transpired. In an angry report, he condemned the authorities and vindicated the martyrs. The surviving three were freed. The decision, however, all but ended Altgeld’s previously brilliant career.

The impact of the tragedy was broad and profound. For decades afterward, the Chicago anarchists were a symbol for workers and radicals around the world. Their heroism and dignity inspired countless others to stand firm for their ideals. The trial and hangings also made clear the fragility of US democracy. In 1886, corporate and government forces united to crush ideas they considered dangerous. The bomb provided an excuse.

The story remains relevant today. Calls for armed struggle, around the world and even in the US, raise hard questions about the legitimate limits of dissent. What should people do when they think the system is rigged, or when peaceful protests meet violent repression?

The Haymarket tragedy was a crucial moment not only in labor history, but also in the long story of humanity’s hopes and errors. The martyrs may have erred in their bold talk about weapons and dynamite. But society betrayed itself by condemning, out of fear, people who represented the aspirations of the poor for justice.

Fortunately, the attempt to smother the spirit of dissent did not succeed. In the end, August Spies was right when he said at the trial, “Here you will tread upon a spark, but there, and there, and behind you and in front of you, and everywhere, flames will blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out. The ground is on fire upon which you stand.”

In 1919, Thousands of people were detained during the Palmer Raids. The rhetoric and scapegoating were much the same as today. J Edgar Hoover was rising fast. “Communism is like a virus,” he charged, “attacking our way of life.” And he developed repressive tactics still used today. Here’s a scene from Inquisitions (and Other Un-American Activities).

Read the Text: Old Times, Same Scapegoats