Through all the races and years Bernie became adept at spinning questions to repeat his carefully honed points, often without directly answering, and remained relentlessly on message. But he was ready to strike back, at the media, or even a member of the public, if he felt defensive or offended.

By Greg Guma

Bernie Sanders is an acquired taste and doesn’t always make the best first impression. I speak from experience. We met in early 1972 at a campaign mixer in the home of a friend in North Bennington. After three years in Vermont this was Bernie’s first political race and he was already aiming for the top — US Senate. He greeted a handful of voters while reclining on a couch, his work boots on the armrest.

Before too long we were having an argument. I wanted to know more about his background and take on Vermont issues. He considered both topics irrelevant and thought I was asking the wrong questions. It was all about “the movement” and capitalism, he insisted, and ended up declaring that he didn't want my vote.

As I retold the story in The People’s Republic, my book on Vermont and Sanders in the 1980s, and later to journalists during his presidential campaigns, I had listened to his analysis of monopoly power and national corruption, and afterward just asked a question.

“Obviously, you haven’t been listening to me,” he shot back. “Do you know what the movement is? Have you read the books? Are you against the war in Vietnam?”

“Yes,” I said, “but you’re a person, not a movement.”

“You don’t understand. It’s the Movement that’s important. Are you for it? If you’re not, I don’t want your vote.” He seemed unnecessarily defensive.

Explaining that I needed to know more about Liberty Union, his political party, and the candidate himself proved useless. Sanders became increasingly irritated with my equivocal attitude. Clearly, this was not a “be here now” kind of guy.

“I don’t need your help,” he said finally. “We don’t have to prove anything to you.”

“You have to prove you’re a basically good person if you want my vote,” I shot back. This was definitely escalating.

Sanders replied, “I don’t want your vote.”

|

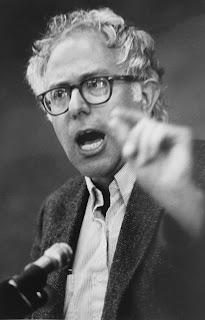

| Sanders in his 30s |

An inauspicious start, to be sure. And memorable enough that I quickly turned it into an article for the local daily. Yet I did vote for Bernie Sanders more than a dozen times in the decades that followed, in races ranging from Burlington mayor to U.S. Congress, Senate and President. Occasionally we would be allies, sometimes not, or we’d meet one-on-one, when he was mayor, to discuss a specific issue. Like the time he wanted advice on how to get a dedicated time slot on the evening news to talk about his accomplishments.

Even before he went “national” I frequently found myself writing about him. Shortly after his March 1981 election, for instance, the Vanguard Press published “Changing of the Guard,” a cover story that explained, as the subtitle announced, “How Burlington Got a Radical Mayor.” Eight years later, another feature, “Eight Years That Shook Vermont,” recapped his mayoral terms. When he donated files to the University of Vermont, I looked through them and summarized what I found in “The Bernie Papers.” And in 1999, when he had been in Congress almost a decade, we sat down privately for a long interview that became “Still Bernie After All These Years.”

As his political style matured, Bernie certainly became more comfortable talking about himself. But he never seemed to lose that angry edge or absolute certainty. In the early days, friends sometimes called him “Total,” a nickname based on how often he used the word in speeches.

Once, crucially as it turned out, I stepped aside in a local election so he would have a clear shot. It turned out to be his first victory. We continued to agree…and disagree. So, yes, it was complicated.

After our poor start, we continued to run into each other at meetings and political events, and basically agreed about the need for radical social change. We just thought differently about the meaning of the phrase — and how to get there.

Once I invited him to write a column about mass media for the Vanguard Press. Among other things, he charged that the owners of the TV industry wanted to “brainwash people into submission and helplessness” and create “a nation of morons.” A fair point, though a bit bleak.

He was blunt, honest, angry and stubborn, and placed the blame for the world’s problems squarely on class and capitalism. He was long on critique but short on practical solutions.

In the 1970s, while I worked as a journalist, and for state and local governments in youth and anti-poverty programs, Bernie ran for governor and U.S. senator, backed unions and activist campaigns, and struggled to make a living as a film strip producer and freelance writer. We sometimes wrote for the same publications.

In 1976, he became the first "third party" candidate in Vermont to force his way into a TV debate broadcast statewide. He was running for governor for the second time. Seated between the Democrat and Republican, State Treasurer Stella Hackel (soon appointed director of the US Mint) and millionaire businessman Richard Snelling (who won the election), he effectively conveyed the idea that there was little difference between them. It still didn't win him many votes. He made the point more effectively in a 1986 race against Democrat Madeleine Kunin, Vermont’s first woman governor, and Republican Peter Smith, founder of Community College. That time he got more than 15 percent, respectable for an independent.

Four years later he was in Congress.

I had moved in a more ecological, entrepreneurial, and local direction. In March 1980, shortly after helping to form the Citizens Party, a new electoral coalition linked with Barry Commoner’s campaign for president, I circulated a memo urging fellow members of the new Vermont Party to focus on Burlington. The state’s largest city “can be extremely fertile ground,” I explained. Financial woes, cronyism between the Democratic mayor and business leaders, unrest among youths, soaring rents — the city’s troubles made it ripe for a political upheaval. “In a three-way race, even a mayoral candidate might be elected,” I predicted.

By then Sanders had left the Liberty Union Party and was organizing low-income residents of Burlington’s Franklin Square housing project, bringing together students, the elderly and poor people to press for affordable housing and tenants’ rights. I was editing the weekly newspaper while planning a possible run for mayor. But as I explained to a Washington Post reporter decades later, “I realized that if leftists had any chance of pulling off an upset, only one of them could be on the ballot.”

Some urged me to run anyway; they considered Sanders a veteran candidate, great at reducing complicated topics to plain English, but more a voice for change in statewide or national races. On Halloween night, however, three of his friends sat him down in a laundry room for a frank talk about his future. In a way, it was an intervention.

As Marc Fisher retold the story during Sanders’ second presidential race, they said that he had no political future if he kept going on as he had. “Sanders readily conceded that, having run for Vermont governor, twice, and for US Senate, twice, never winning more than 6 percent of the vote, he risked getting stuck on the fringe, perceived as a joke.” He also had trouble connecting with the people around him. “Without a steady job, he drove around the state in his Volkswagen Bug trying to sell teachers the films he had cobbled together about socialist Eugene V. Debs and other radicals.”

As he entered a second decade of campaigning, Sanders wanted another shot at running for governor. His friends didn’t like the idea. Richard Sugarman, a philosophy professor who taught existentialism and Jewish thought at the UVM, joined with the others in urging Sanders to give up on fruitless statewide races and instead target Burlington, a place where he might actually win.

Sugarman had run the numbers. Although Sanders never came close in any of his 1970s campaigns, he had scored 12 percent in the state’s largest city. And he had done especially well in Burlington’s lower-middle-class neighborhoods. I’d also run some numbers and knew that Robin Lloyd was doing even better. Less than two weeks later, she won 25 percent of the Burlington vote in her Citizens Party campaign for Congress.

“Sanders was blunt,” Fisher wrote. “He knew little about city issues, couldn’t see himself as the guy in charge of snow removal. But the others insisted that a mayor could focus on matters Sanders cared about.”

They argued through the night. “Sanders repeatedly said he wanted to focus on big, systemic change. But he also wanted to break out of his identity as a perennial also-ran.” In the end, he decided they were right; it was better to run for mayor. But he had another question for his friends.

“What the hell would I do if by some miracle I won?”

About a week later, he called me at the newspaper and we met to “suss out each other’s plans,” Fisher continued. “Bernie said, ‘I’m running,’ Bouricius explained. ‘This is not an educational campaign.’ He was in it to win it, and he needed a clear field.”

Actually, Bernie didn’t say any of that when we met. “I’d make a good candidate” is how he actually put it. He did admit that he didn’t know much about local issues, yet showed little interest in what I thought about them. I told him anyway.

Despite the warning years earlier by my wife Josi that I wasn’t “white enough” to become mayor, I was seriously considering the race until that moment. But if I ran, I was very likely to lose my job. Some at the weekly disapproved of journalists having anything to do with electoral politics. As I told Fisher, “The owner of my paper didn’t want me in politics. Bernie didn’t have anything to lose — no job. And he’s 6-2 and I’m 5-5, and that makes a difference.” He was also battle-tested and a more natural politician, while I had a job that I enjoyed and wanted to keep.

Later in November, I publicly announced my withdrawal from the race. The Citizens Party nominated me anyway at a citywide caucus the following January. I declined, instead joining an ad hoc coalition with Sanders, and ran for the City Council. In addition to editing the Vanguard Press, I chaired the local branch of the new party.

Shocking almost everyone, Sanders won the mayor’s race by just 10 votes, 40 percent in a four-way race. I lost with 42 percent in a two-way race against the chairman of the local GOP and returned to the editor's desk. But Terry Bouricious won a City Council seat, the first Citizens Party victory in the country. More members of the party took Burlington Council seats in the following elections.

It was the start of multi-party politics in Vermont and led eventually to the formation of the Vermont Progressive Party, the most successful alternative to the two major parties in the country. Over the next 40 years, its candidates won numerous local, legislative and statewide elections.

Poisoned Press

The dirty tricks began right after the 1981 election. Within days, a new “underground newspaper” was launched in Burlington. But you couldn’t get it at a newsstand, or anywhere public. And the content was designed to discredit rather than inform.

Named after the Gannett-owned Burlington Free Press, the city’s only daily, the Flea Press reached an “elite” audience in the hundreds on a weekly basis, or thereabouts. City officials and media received it in the mail. According to then Assistant City Clerk Patrick Sullivan, copies of the photocopied publication would arrive near the end of the week, in time to reach city council members before their Monday public sessions. It quickly became the water-cooler talk of the town.

The Flea Press came in “a legal-size manila envelope,” Sullivan recalled, “with sealed envelopes inside addressed to the individual aldermen.” The postmark changed every week. It was a little like how porn was delivered. Additional copies were distributed hand-to-hand inside City Hall, read and re-duplicated by the curious and amused.

When the City Council met that May, Allen Gear, a Republican on the Board, personally passed out copies from a stack in open view. And when he and Democrat Joyce Desautels charged that evening that Sanders was trying to advance “the Socialist Party” in Burlington, their rhetoric closely resembled the editorial line of City Hall’s new, unofficial house organ.

In the Flea Press world, most local media ranked near the top of an “enemies list.” Early issues roasted editors and reporters at both the Free Press and Vanguard Press, the alternative weekly renamed Rumpguard Press. I was another frequent target. Collectively, we were blamed for the defeat of “Gordon H. Pickett” (Paquette), the “luckless incumbent.”

In fact, the first issue charged that political reporters had conspired with the Free Press ad department “in electing the city’s first Marxist mayor.” In the second issue he got a name — Burns A. Sunder.

By April, mild lampooning had turned into serious, often nasty personal attacks. Long before Twitter, nicknames were a cruel and effective way to ridicule the new personalities in local politics. The most consistent target, beyond the mayor himself, was “Pritchard Sauersmail,” often described as “Deputy Mayor.” Most readers knew that the actual target was Richard Sartelle, a Sanders ally and local low-income housing organizer whom the new mayor was paying — out of his own salary — to act as a community liaison.

The anonymous editor-writer of the Flea Press, who often betrayed a visceral distaste for “Sauersmail,” even stooped to belittling his clothing, family and intelligence, while chiding City Councilors for failing to take away his “free office space plus telephone.”

Eventually, the attack went mainstream. After the Flea Press smeared “Sauersmail” in six consecutive issues, the Burlington Free Press echoed its stance with a call for his removal. An editorial supported the case by arguing, without evidence, that unnamed city employees might view the Sanders associate as an “unofficial deputy mayor.”

Despite a few unique twists, the tactics were familiar. Mixing facts, slander and conspiracy theories was time-tested, a toxic combination employed in the FBI’s counterintelligence campaign against the anti-war movement and New Left. In the late 1960s, anonymous mailings and leaflets also used humor to ridicule targets, mainly opponents of government policies, and to spread disinformation.

The difference in Burlington was the insider perspective. The author of the Flea Press knew too much about activities inside City Hall to be a complete outsider. The jokes and gossip focused sharply on about a dozen key people and groups closely allied with Sanders. Many people assumed that a city employee somehow had to be involved.

Battle lines were being drawn, and the issue that best exemplified the dynamic was the appointment of city officials — normally a mayoral prerogative, but subject to City Council approval. Sanders wanted to replace six out of 20 key people, mostly through attrition. Yet, on reorganization day, his candidates were rejected without a single question about their qualifications. The unspoken message was that “stonewalling” would be the order of the day.

Burlington’s new “underground press” captured and amplified the hostility. Its targets ranged from a police officer renamed Jody Kreepso, stand-in for a Sanders supporter who had been demoted, to Gov. Prinz Philip (Phil Hoff), who embraced the new political energy in the city. After a while, “old guard” city workers began to use the nicknames in public. On the phone one day, the police chief accidentally called a reporter by his Flea Press name.

Of course, Burlington’s “underground” also had friends, especially former Mayor “Pickett,” stalwarts like City Treasurer “Austin F. Lee” (Lee Austin), Police Commissioner “Applewater” (Antonio Pomerleau) and City Clerk “Francois Vagon” (Frank Wagner).

At first considered no more than a nuisance, the Flea Press gradually began to look more threatening. It was making red baiting acceptable. At times other media outlets even began to sound a bit like the publication that mocked them. When Sanders debated City Council members about his proposed appointees, for example, the Burlington Free Press described them as a “tight cadre of comrades.”

There was no attribution for the loaded phrase, a not-so-subtle reinforcement of the notion that Sanders was running a “socialist administration.”

How the system works

Bernie was well aware of the low-level red scare underway in early 1981, and wasn’t eager for a fight so soon into his first term. But he didn’t dodge the issue either, and decided to offer some of his earliest public remarks about socialism — less than three months after becoming mayor — as part of a welcome for Andrew Pulley.

The 1980 presidential nominee of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) visited the Queen City on May 21, 1981. Sanders had been one of Pulley’s electors in the recent presidential race. Now the former candidate was on tour to discuss a lawsuit filed by his party against the federal government.

Here are some of Sanders’ remarks that night, as recorded and transcribed by the SWP’s newspaper, The Militant:

I’m sure most of the people here know that for the last forty years the Socialist Workers Party has — now admittedly — been harassed, informed upon, had their offices broken into, had members of their party fired from their jobs, and have been treated with cold contempt by the United States government.

And it’s very clear that the reason they have been thus treated is because of their ideas — ideas which are frightening to the people who own the United States of America.

And they are a threat, these ideas, they are a threat.

I think the point Andrew will probably deal with is also well known. In the fifties, with McCarthyism, they created a system of bugaboos, with the bugaboo of communism. Any person who stood up for working people, or for low-income people, or for peace, was associated with the “communist front.” Now the word is “terrorist.”

Now anybody who stands up and fights and says things is automatically a terrorist and to be associated with these people who plant bombs in buses, and murder children and innocent people.

I trust that many of you know how the system works. It happened slightly, in my case. Because I was an elector for the Socialist Workers Party, there was a “non-investigation.” I was “non-investigated” by the FBI. The theory is that it was an attempt to smear me.

I think there’s a way to deal with that terrible word — that pornographic word which they hate in this country — called socialism.

Sanders advised those who attended to be straightforward about socialism, but also to talk about democracy. “I don’t have to go out denying it,” he said. “Then we can have the debate which is the real debate all around the country. That debate is socialism versus capitalism. That is the debate of our century.”

“I think the best way is to be up front about that word,” he advised, “not to run away from that word. To deal with it in a straightforward way, and explain exactly what we mean by that word.” This is essentially what he has done as a presidential candidate.

“Along with Andrew,” he added, “we are anti-authoritarian. We believe in democracy.”

Speaking with Harry Ring, a reporter for The Militant, Sanders also added, “This garbage about people ‘don’t want’ government. Of course people want government to do something for them. But they don’t want the kind of government they’ve been getting.”

“I think most people understand that there aren’t two parties. That there’s just one party called Republocrats, or Demicans, or whatever you want to call them.” But in Burlington, he added, “at least we’re bringing the word socialism into the realm of reality. It’s no longer some far-off business.”

Actually, the word was spreading as America’s only socialist mayor since the Depression fast became a national sensation. A clear sign was his July 1981 “appearance” in Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury, in the form of an imaginary TV encounter with “Tomorrow Show” host Tom Snyder.

“Mr. Mayor, let’s be candid okay?” asks Snyder. “You’re a socialist. You’re a Jew. You’re from New York. So how the heck’d you get elected?”

Bernie’s reply was typically blunt. “The people of Burlington wanted a change. They decided to send the capitalist system a clear message.” Then there’s a joke about France and the fringe benefits of being mayor.

Not everyone was so intrigued or accepting. A May issue of the Flea Press featured a poignant article by “Jeems I. Weezleson” (Free Press editor James Wilson), who revealed his yearning for the former mayor’s return:

“In striking contrast to the mayor’s appearance was the presence of the Honorable Gordon H. Pickett, former Queen City mayor, and the association’s (Queen City Downtown Merchants’ Business Association) first annual award recipient. Senator Leamy (Patrick Leahy) was unstinting in his praise for the former mayor and the association seconded it by giving Pickett a ten-minute standing ovation.”

It was a slight exaggeration. Yet, having captured an underground base in City Hall, the Flea Press was turning anti-Sanders holdovers and employees into its distributors. The format was refined a bit, a typeset masthead proclaimed it “A. Ginnit Newspaper,” and cartoons were added under the headline, “Goonsbury.” The content remained the same, a grab bag of gossip, labels and lies designed to anger and demean, a sophomoric merger of the National Enquirer and Harvard Lampoon.

People working in neighborhood groups were “residential hyper-active groupies,” roasted for either their looks or alleged moral failures. Predictably, the anti-Sunder majority on the City Council could do no wrong. In June, however, some concern was expressed in the Flea Press that the new mayor might get his appointees after all. “Sunder is counting on cupidity, middle-class stupidity, and terror tactics to crack the aldermanic front,” its editor speculated.

Perhaps this was a premonition. By August attitudes were indeed changing. A Republican, Robert Paterson, called the Flea Press “insulting and in bad form,” and Joyce Desautels, who once echoed its rhetoric, now considered it “a bore,” although she did like the cartoons. “Burns A. Sunder,” the “Queen City’s Marxist Potentate,” was still lampooned and labeled a “red.” But a new Enquirer-style obsession had emerged — the mayor’s personal relationship with “Jean Dripsoil” (Jane Driscoll, now Jane Sanders).

Exposure and realignment

For six months, theories circulated about who was behind the weekly slander sheet. It had to be someone close to city affairs, in fact someone who had mourned with the Democrats on election night. Close analysis of Flea Press content revealed attendance at budget meetings and other city functions, along with deep contempt for neighborhood groups and the local press.

But few knew the truth. That is, until a paste-up of page two was left behind on a copier only blocks from City Hall.

At first pollster Vincent Naramore denied having left the page. “Well, did anyone see me do it,” he snapped when confronted. But absolute denial eventually became “I can’t remember” making copies on the day in question. And anyway, the Vanguard Press had the document.

Naramore had good reasons to avoid exposure. A math professor at St. Michael’s College in Colchester as well as a well-known pollster, he was also a past chairman of the city Democratic Committee. Beyond that, he frequently attended morning coffee gatherings at Nectar’s restaurant with local party insiders, including the ex-mayor, and the current City Clerk and Treasurer. Another frequent Nectar’s attendee was Brian Burns, former lieutenant governor whose brother was on the council and possible Sanders challenger in the next election for mayor.

And there was more. Naramore’s sister-in-law worked in the City Clerk’s Office. Naramore himself had accompanied Mayor Paquette on an election-day tour of city polling places. But he was neither a pollster nor an adviser to Paquette at the time, he claimed, “just a close friend.”

After Naramore’s exposure as editor, the Flea Press immediately vanished, never to return. But the poisonous atmosphere it had helped to create lingered on, in City Hall and beyond. Through most of 1981, Sanders had to endure working with hostile staff, including two of Naramore’s close friends (and probable co-conspirators), City Treasurer Austin and City Clerk Wagner.

But the past was catching up with the last administration. In October, the Vanguard Press published my investigative cover feature “Highway Robbery?” The subtitle proclaimed, “State Law Dodged to Fund Southern Connector.” As the lead explained, the Vermont Highway Department had been spending money on Burlington’s controversial connector road for three years. But state highway officials knew that the city hadn’t allocated local funds in time to meet a legal deadline.

Documents obtained by the newspaper showed that Burlington officials, including former Mayor Paquette and Wagner, were aware of the deadline. So aware, in fact, that Wagner wrote a letter to a highway planning official falsely claiming that “voters of the City of Burlington approved the local portion of the cost for the project at the Annual City Meeting held March 1, 1977.”

No such vote had taken place. The public wasn’t asked for bond authorization until 1979, six months after the deadline. But the state Highway Department accepted the statement and never asked for further proof. After the Vanguard story appeared, however, Wagner went on vacation and never returned to work.

A few months later, a hundred progressive volunteers canvassed the city and staged an impressive get-out-the-vote effort. When the votes were tallied that March, Sanders had five supporters on the City Council, up from two, and there was no denying that Burlington had a multiparty political system. Rik Musty and Zoe Breiner joined Terry Bouricius in the Citizens Party group; Gary DeCarolis, who had lost to Sanders supporter Sadie White in 1981, now joined her as an independent.

It took four more years for this loose organization to become the Progressive Coalition. But it had demonstrated that Sanders’ election was neither a fluke nor a socialist revolution, but instead the beginning of a political realignment.

In 1983, only days before the next mayoral vote, Sanders’ Republican opponent played the Socialist card one more time. WARNING! shouted the headline of a full-page ad in the Free Press. If Bernie won a second term, it charged, the consequences would be dire.

“Mayor Sanders is an avowed Socialist,” the GOP ad accused. “Socialist principles have not worked anywhere in the world … They won’t work in Burlington either.”

It was a desperate move that suggested Sanders’ leadership would produce everything from higher electric bills to more unemployment. And it turned out to be a major tactical mistake. Burlington voters had seen him and other progressives in action for two years, and rejected the hysteria and negativity. On March 1, he won a clear majority of 52% in a three-way race. Progressive politics was in Burlington to stay.

Reflecting on his first victory in 1981, Sanders concluded, “I think we had pretty much of a class vote.”

Agreeing to Disagree

Throughout Bernie’s eight years as mayor we were sometimes coalition allies. But we also disagreed on development and peace issues. At one point that meant he presided over my arrest (with many others) outside an armaments plant. Peace groups were protesting Gatling gun production and pushing for economic conversion. He felt we were blaming the workers and should protest instead at a congressional office.

On the day of the sit-in, he was sullen and conflicted. He argued with the chief of police about videotaping the protesters, but also criticized an attempt to defuse the situation by asking General Electric not to ship arms for the day. The night before the event he contacted me to warn that the chief’s assurance about no shipments was inaccurate. He had demanded that the company be told to conduct “business as usual.”

Three years later, in 1986, he had been mayor for five years and saw a chance to run for governor. But the Democratic incumbent was Kunin, who had been in office less than two years as the state's first female chief executive. In the end, I couldn’t support Bernie that time and instead found myself role-playing him in a private mock debate with Kunin.

Decades later, Michael Kruse focused on this period for a Politico story, particularly on the relationship between Bernie and Jesse Jackson, who ran for president in 1984 and 1988. By 1986, as Kruse explains, “the Rainbow Coalition that Jackson’s ’84 campaign had spawned had grown in power in Vermont. Sanders, who was running for governor, couldn’t ignore it. Nor, however, could the state’s energetic contingent of Jackson devotees avoid Sanders, considering the sway he had over progressives in Burlington and beyond. A symbiosis between the two outsiders started to materialize.

“Sanders didn’t join the Rainbow; he wasn’t much of a joiner, period. But he ‘realized the necessity of participating in broader coalitions if he was ever to take his vision beyond the city limits,’ progressive organizer and journalist Greg Guma of Burlington wrote in his 1989 book, "The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution." ‘He was looking to hold onto that base of support so he could challenge from the outside,’ Guma told me.”

After four terms, Bernie retired from his role as mayor —as it turned out, to prepare for the next chapter, national office. After a defeat by Republican Peter Smith in a 1988 congressional bid, he came back two years later and won. That led to eight terms in Congress — before moving on to the Senate. He didn’t lose another race until his first campaign for president in 2016.

Meanwhile, I went on to edit other publications; defend immigrant rights in New Mexico as director of a legal rights organization; manage an eco-feminist bookstore in Santa Monica, California; launch Vermont Guardian, another Vermont weekly; and manage Pacifica Radio, the progressive listener-supported network.

In 1998, while working for The Vermont Times, I interviewed Bernie privately about his philosophy and plans. By then he had made peace with the Democratic Party, often a target during his third party and Burlington years. But he could already envision a run for president and was certain he would "do well."

Summing up his concerns in another era of scandals and corruption, Bernie explained, “You have two political parties that are controlled by monied interests. You have a corporate media. When you talk about consolidation, you are talking about oil and gas, banking, and perhaps most importantly, the media – where there are very few voices of dissent regarding our current position on the global economy."

“That gets to even the more fundamental issue – the health of American democracy," he said. "Do people know what’s going on? And how can they fight what’s going on? I fear that they don’t.”

Through all the races and years he became adept at spinning virtually any question to repeat his carefully honed points, often without directly answering, and remained relentlessly on message. But he was ready to strike back, at the media, or even a member of the public, if he felt defensive or offended. I'd even seen him shut down a press conference when he didn't like the way things were going.

It happened again in 2011, the last time we were in a small room together. The topic was Lockheed Martin and its relationship to Sandia Labs, which he was welcoming to Vermont.

In the mid-1990s, Bernie had led the charge against $92 billion in bonuses for Lockheed Martin executives after the corporation laid off 17,000 workers. He called it “payoffs for layoffs.” In September 1995, after his amendment to stop the bonuses passed in the U.S. House, Lockheed launched a campaign to kill the proposal.

In 2009, he was still going after Lockheed in the Senate, calling out its “systemic, illegal, and fraudulent behavior, while receiving hundreds and hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer money.” By then, however, he had visited Sandia headquarters and came away eager to have a satellite lab in Vermont.

At the end of 2010, days after a mini-filibuster that jump-started a “draft Bernie” for president campaign, Burlington Mayor Bob Kiss announced the results of his own Lockheed negotiations, begun at billionaire Richard Branson’s Carbon War Room. It took the form of a “letter of cooperation” to address climate change by developing local green-energy solutions. Lockheed later backed out.

By 2011, however, Sanders was also supporting the Pentagon’s proposal to base Lockheed-built F-35 fighter jets at the Burlington International Airport. If the fighter jet, widely considered a massive military boondoggle, was going to be built and deployed anyway, Sanders argued that some of the work ought to be done by Vermonters, while Vermont National Guard jobs should be protected. Noise impacts and neighborhood dislocation were minimized, while criticism of corporate exploitation gave way to pork barrel politics and a justification based on protecting military jobs.

When Vermont’s partnership with Sandia was officially announced on Dec. 12, 2011, Gov. Peter Shumlin didn’t merely share the credit. He joked that Bernie was “like a dog with a bone” on the issue. But the launch ended abruptly after a single question about the city’s aborted partnership with Lockheed Martin. Before a TV reporter could even complete his query Sanders interrupted and challenged it. Lockheed is not “a parent company” of Sandia, he objected.

And then, as is often the case when faced with unwelcome questions, he declined to say much more – about Lockheed Martin or the climate change agreement Mayor Kiss had signed, the standards adopted by the City Council, the mayor’s veto, or Lockheed’s subsequent withdrawal from the deal. Instead, he turned the question over to the representative from Sandia, who offered what he called “some myth-busting.”

It was more like an evasion. All national labs are required to have “an oversight board provided by the private sector,” he explained. “So, Lockheed Martin does provide oversight. But all of the work is done by Sandia National Laboratories and we’re careful to put firewalls in place between the laboratory and Lockheed Martin.”

In other words, trust us to respect the appropriate boundaries, do the right thing, and follow the rules. Moments later, Sanders announced that the press conference was over.

After his two presidential campaigns and despite repeated protests and local votes opposing the arrival of F-35s, twenty fighter jets were bedded at the Burlington airport. Bernie continued to avoid the issue. In 2023, he was again thinking about running for president.

Below: In 2012, Gov. Peter Shumlin and U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders announced the launch of a satellite Sandia Lab in Vermont. “He was like a dog with a bone,” Shumlin joked.