EXCERPTS FROM MANAGING CHAOS

REVIEW: WHO WILL TELL US THE NEWS?

Norman Stockwell, The Progressive

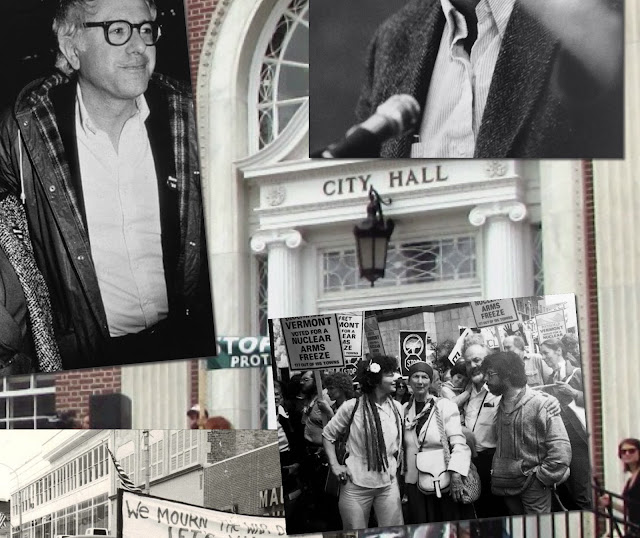

BY GREG GUMA

Around the time I turned 21, Sen. J. William Fulbright described what was taking place across the country as a “spiritual rebellion” of the young against a betrayal of national values. Almost half the US population was under 25 at the time. I’m not sure how spiritual they were, but, speaking personally, I did feel betrayed, conflicted and rebellious.

It was March, 1968, and the US Senate had opened an investigation on the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, passed four years earlier. The resolution had given President Johnson a blank check to wage war in Vietnam, based on a trumped-up military incident. Half a million troops were mobilized as American leaders used communist fears and falling dominoes to rationalize a major invasion.

The operative logic was that it might be necessary to destroy the country in order to save it.

|

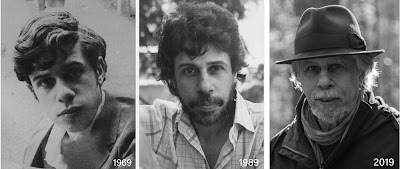

| Anti-war protest at the Bennington Monument (GGuma/1969) |

For a moment the storm clouds parted. Eugene McCarthy, an ardent opponent of the war, won an encouraging 42 percent of the Democratic Presidential primary vote in New Hampshire. Four days later, Robert Kennedy officially entered the race. By the end of the month Johnson announced that he wouldn’t seek re-election. It felt like history was speeding up and moving forward. But on the same day Kennedy announced his run, American troops lined up hundreds of old men, women and children in a South Vietnamese village, Mai Lai, and killed them. It was one of several massacres that were hidden for two years.

Just as the country looked for a way out, it was losing its soul.

In the midst of this chaos the prescient muckraker I.F. Stone wrote something in his weekly newsletter that stuck with me. “Everywhere we talk liberty and social reform,” he warned, “but we end up by allying ourselves with native oligarchies and military cliques — just as we have done in Vietnam. In the showdown, we reach for the gun.”

As if hammering that home, a few weeks later, two months before I graduated from Syracuse University, a shot rang out in Memphis and ended the life of Martin Luther King Jr. A political assasination, five years after the death of President Kennedy, this one was possibly linked to a racist (and perhaps FBI) conspiracy. In the days that followed, riots erupted in at least 125 American cities, resulting in more than 20,000 arrests and the mobilization of federal troops and the National Guard. Like millions of others, I was stunned, confused, angry, and scared. Two months later, just after I moved to Vermont, Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles on the night he won the California primary.

The war had come home with brutal violence and death. In the first five months of the year, almost 10,000 soldiers died in Vietnam, more than in all of 1967. By July, there had been over 200 major demonstrations on campuses across the country. Yet despite the obvious signs of domestic unrest, especially about the war, it continued to escalate. And the domestic repression was just beginning.

After my last classes and a few goodbyes, I didn’t even hang around for the graduation ceremonies. Instead, I packed a suitcase, stored my Yamaha bike, and drove to Bennington. Nestled between Albany and Western Mass in southern Vermont, it felt like an escape from the urban rat race, high-energy aggression and ruthless competition, mass anxiety and gnawing fear.

Out there, but not too far…

a media saga, personal story and cautionary tale

|

| MAVERICK BOOKS, 317 pages, illustrated |

Now Available in Paperback: Order Here

For review copies, send name, address and $8 to MavMediaVT@gmail.com

View sample on Amazon

Managing Chaos: Adventures in Alternative Media — an eye-witness account that explores the unique, tumultuous history of Pacifica radio and alternative media in America. Filled with episodes from an eclectic career, Greg Guma’s new book discusses the evolution of radio and television, the impacts of concentrated media ownership, the rise of the alternative press, his complex relationship with Bernie Sanders, his work in Vermont before and during a progressive revolution that changed the state’s power structure, and decades later, what happened while he managed the original listener-supported radio network. Here is another excerpt.

Siege Mentality

In-person meetings of Pacifica’s national board were all-weekend affairs. Really more than a weekend: Managers and staff began arriving Wednesday for a full-day, staff-only summit on Thursday. Held every three months, these quarterly rituals took considerable energy and preparation time.

The location rotated according to a mandated sequence, another bylaw restriction created by the reformers who recaptured the network, evidently designed to equalize local participation. The trouble was that housing dozens of people for days in a venue like New York, plus a meeting space large enough to accommodate an audience and “public comments” from activists, could cost double the price of the same digs in Houston. But a summer session in Texas could be unbearable. It was arbitrary, uncomfortable, and sometimes unnecessarily costly.

On the other hand, the gatherings brought together people from disparate communities and cultures across the country. If the vibe was right, an in-person PNB meeting could build momentum behind new ideas. My plan for the March 2006 session in Los Angeles, two months after I started work, was to lay out problems and win early “buy in” for a network-oriented response. Not to reach consensus. It was more like critical mass.

As Affiliates Program Coordinator Ursula Ruedenberg delicately put it during a “thematic” discussion that weekend, national programming “is very thorny just beneath the surface. It set the stage for what happened in the ‘90s. There began to be pressure to work as a national network,” she recalled, “and that process aroused all sorts of issues.”

The timing and location looked right. The board was about to adopt a National Programming Policy, which would trigger the hiring of a coordinator. Theoretically, he or she could pull together people and programs across the country. Meanwhile, outside the hotel in the streets of Los Angeles, over a half a million people were gathering for “La Gran Marcha,” part of a nationwide protest against a proposed law to raise penalties for illegal immigration and classify the undocumented — or anyone who helped them — as felons.

Over the next few days hundreds of thousands also showed up for rallies in places like Denver, Cleveland, Columbus, Detroit, and Nashville. In the wider debate over immigration these protests not only demonstrated opposition to the bill, they called for a “path to legalization” for the millions of people entering the country without documents or permission.

Living in Los Angeles more than a decade earlier, I’d watched immigration politics play a role during the riots of 1992. Border Patrol cops deployed in Latino communities arrested more than 1,000 people. Afterward, the INS began work with the Pentagon’s Center for Low-Intensity Conflict and the line between civilian and military operations was largely erased. Human Rights Watch accused border cops of routine abuse, a pattern of beatings, shootings, rapes, and deaths. In June 1995, detainees in a private jail had rioted after being tortured by guards.

In some ways, Southern California embodied both the American Dream and the right’s cultural nightmare. A confluence of climate, capital and demographics had made it an international zone and the world’s image capital. By the early 21st century, the City of Angels was populated heavily by brown and black residents, many of them recent immigrants. It would soon be more than 40 percent Hispanic, 12 percent Asian, 10 percent Black, and less than 40 percent European-American. As David Rieff noted in his book, Los Angeles: Capital of the Third World, the rest of the country, and possibly the world, would likely follow the L.A. model.

Moving to New Mexico in 1996, I ran a non-profit that provided legal support for both legal and undocumented immigrants. By then the border had become a battlefield. Government strategies for combating undocumented immigration had remilitarized the entire region. The recently-passed North American Free Trade Agreement meshed neatly with more obvious aspects of low-intensity conflict doctrine. The definition of immigration and drug trafficking as “national security” issues brought military thought and tactics into domestic affairs. Just as the projection of a “communist menace” had been a smokescreen for post-war expansionism, a “Brown wave,” the “Drug War” and terrorism were used as pretexts for military-industrial penetration.

Immersing myself in immigration law and regional race politics, I developed a coalition of sympathetic groups to fight back against the most draconian aspects of a new immigration reform law. We staged public rallies in Albuquerque, and brought Latino and Asian spokesmen to Santa Fe to testify at legislative hearings.

Defending the rights of immigrants was a perfect focus for Pacifica, and the national board promptly took time out to join the march. For KPFK it was a golden programming opportunity. The station went live for five hours that day, airing reports and coverage in Spanish and English, the first show of its kind. Yet the other sister stations didn’t take it as a national feed, preferring local coverage or the usual shows.

Latino programming was at the top of the agenda. Largely at the urging of KPFK, the board had decided that a daily Spanish language news show should be launched nationally. New York and DC Latino activists were lobbying for more airtime. They had a practical point. The demographic trends in signal areas and nationally pointed to a large “under-served” audience. According to Arbitron, Latinos spent more time listening to the radio than any other ethnic group.

In fact, Spanish-language media — Univision, Telemundo and radio stations — had helped to mobilize people for the immigration protests. In L.A. , Eddie “Piolin” Sotelo, a Spanish radio personality, persuaded friends at other stations to rally listeners and cover the event. But commercial radio’s interest in the issue was likely to fade, while Pacifica, if it made a sustained commitment, could build a large and loyal new listenership.

“I’m feeling a lot of pressure for change,” I told the board, “people waiting to see whether I will take sides, and waiting to judge. I’m bound to disappoint some people. There’s really no way to satisfy all of the expectations.” It might be possible to find common ground, I allowed, but winner-take-all wasn’t the best starting point.

“What we have, with certain exceptions, is a siege mentality,” I reminded them, “sometimes referred to as protecting turf.”…

From the Epilogue

Pacifica had been through a decade of internal struggle when I arrived in Berkeley. Worried about a possible corporate takeover, members of the staff, board and volunteers at the stations had fought back, and eventually created a new, more democratic governance structure. You might even call it hyper-democratic. But also incomplete, unwieldy and difficult to amend. It didn’t prevent factions from forming at various stations. In fact, it seemed to produce contested board elections and bitter charges that the process was unfair, even rigged.

In January 2006 the organization was battle-weary, but recovering and financially stable. The next two years were more peaceful than most. But the animosity and tribalism didn’t vanish. Rather than become the center of yet another internal power struggle, I stepped aside to make way for the next chief executive, someone who had been fired years before.

As it turns out, she didn’t appreciate the new democratic structure and stayed for less than a year. Six years after that, one of her successors barricaded herself inside the national office rather than accept a replacement. The mood had gone from suspicious to openly hostile.

Personally, it was a productive decade. Despite the warning before becoming ED, I did work again. Once back in Vermont, I returned to writing and journalism, and wrote about Burlington and national politics for VTDigger.com, a new online platform that established itself as a leading news source. Gannett still owned the Burlington Free Press, but it was no longer a Vermont media leader and not much of a daily. Now a top news source was Seven Days, a robust print weekly that succeeded the Vanguard Press and provided breaking news through an effective online platform.

After the Democrats resumed control of City Hall, I also ran for mayor, something I had postponed for decades, ever since stepping aside for Bernie.

Chapter One: Excerpt

Other Excerpts: The Road to Change