Altered States: How 42 governors, the Secret Service, and two presidential candidates ended “welfare as we know it.”

By Greg Guma

By the time Bill Clinton and Bob Dole arrived in Burlington to discuss welfare reform, the 1995 National Governor’s Association annual meeting had become a high-security photo op. The President and Senate majority leader, Clinton’s main challenger in the upcoming presidential race, had obviously begun their campaigns. The Secret Service was acting accordingly.

Not since the masters of international finance capitalism took over Laurence Rockefeller’s estate, and most of Woodstock, back in 1971 had there been so much heat in Vermont — with so little light.

|

| Bill Clinton speaks at the 1995 NGA meeting in Burlington. |

To those who watched on C-SPAN in early August, the conference may have looked like a serious effort to grapple with federal-state relations and reach an agreement on welfare reform acceptable to state leaders, Congress and Clinton. The buzzword of the weekend was “flexibility,” and the dominant refrain that, once the block grants came tumbling down, governors wanted them with as few strings as possible.

The host, Vermont Gov. Howard Dean, was hoping for something “genteel,” as he put it during a press conference opening the weekend, and above all uneventful. Potentially, it might also be a final feather in his cap as NGA chairman before turning over the reins to Wisconsin Gov. Tommy Thompson.

Despite the official agenda, however, the NGA’s annual meeting was more about appearances and networking than policies. The presence of business executives and lobbyists, identifiable by their “corporate fellow” badges, rows of TV cameras, special guests, and hundreds of stoic state and federal police conveyed a weightiness that the actual content did not merit.

Yet there was a substantive debate that weekend — between officials and thousands of protesters who thought that Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America” was hazardous to the nation’s health. In a series of public events, they raised issues not on the program. They noted, for example, that despite all the talk about welfare “fraud” and saving money, only about one precent of the federal budget at the time was actually devoted to such programs. They also pointed to a wave of attacks on the reproductive rights of poor women.

When Gov. Thompson talked about flexibility, for example, what he meant was the right of states like Wisconsin to deny public support for new-born children. It was called the “child exclusion” program, allowing states to deny federal AFDC benefits to women having children while receiving support. Clinton promised to do more of the same, like fast-tracking funding waivers for states that met his reform criteria.

Predictably, the “dialogue” between protesters and the powerful didn’t find its way into most press reports. A few journalists did juxtapose official pronouncements with protest coverage, mentioning a People’s Conference held nearby in Battery Park and a subsequent series of arrests. But the focus was mainly on the “right to dissent” rather than the point of the protests. Form was clearly more interesting to mainstream media, and easier to cover, than content.

That was fine with the governors. For most, the “Contract” was already the new normal. Why debate anything? After all, the point of the weekend, as described by veteran Vermont pol Tim O’Connor, was to create a friendly atmosphere where elected state leaders can get past their differences. Yes, these were the good old days.

O’Connor and I were on the Burlington waterfront, watching security dogs sniff for explosives under a big tent prior to a dinner gala. Moments later governors began shuttling down from the conference site. Marksmen kept the area under surveillance from the rooftop of the city’s new ECHO science center.

Security had been tightening all day, especially after protesters took the police by surprise at the Radisson Hotel. Just as the School-to-Work Roundtable broke up, giant Bread & Puppet Theatre heads peered over the hotel driveway. More than 2,000 people followed them, marching by as they chanted “Hey hey, ho ho, the Contract has got to go.” A few governors strolled out to catch the parade.

But the mood turned tense when a faction, led by people opposed to the looming execution of radical black journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal, advanced to the doorway. A police cordon was hastily assembled and the confrontation became an impressive show of self-controlled people power that challenged the mood of elite camaraderie inside.

After that, the Secret Service took no chances. They quickly brought in reinforcements and commandeered cops from surrounding communities. When the protesters returned to confront the governors at dinnertime, a barricade kept them two blocks away.

Unlike most locals, I got to witness the spectacle from a privileged perch: member of the press. I had obtained a blue badge and a parking plaque that said “official business” without much fuss, by presenting only a driver’s license and press pass produced by the World Service Authority, a world government organization that issued documents more convincing than the “real thing.” Fortunately for the President and everyone else, no violent extremists thought of this. Yet the troubling truth was that almost anyone could have crashed this party, parking a station wagon full of explosives about 30 feet from the podium in the Sheraton’s Emerald Ballroom. That was high security before 9/11.

Two activists did manage to penetrate the security perimeter during Dean’s opening remarks on Sunday, yelling “free Mumia” right beyond the ballroom doors. Meanwhile, outside in the parking lot, more than a dozen protesters in wheelchairs also got past a police line. They were cited for trespass.

That said, the NGA was concerned enough about possible disruptions to deny credentials to Michael Moore, the famous filmmaker, then hosting a Fox television series called TV Nation. He had come to town, he explained, to get closer to power, close enough to hug as many governors as possible. Rebuffed by staff, he showed up on the waterfront, and was surprised to learn that other “alternative” types like myself had managed to gain entry.

|

| Michael Moore looked for an opening on the waterfront. |

Our encounter, which became a vignette on Moore’s show, underlined the arbitrary, paranoid and ultimately ineffective nature of conference security. But what the police were really protecting the officials from wasn’t the threat of physical violence. It was the danger of unanticipated questions.

Thompson mumbled some reluctant support, but added that “other things are more important.” He seemed to be hedging on a key plank in the right-wing platform, so I went to his press secretary for a clarification. I didn’t get it, but two days later one did come in Thompson’s introduction of Dole. The senator “is determined to breath life back into the 10th Amendment,” Thompson announced, “and to end unfunded mandates.” Important or not, the governor was back on message.

Already on the campaign trail, Dole was primed to pander. He talked about how states are “closer to the problem,” and how block grants shouldn’t have to deal with “rules inhibiting innovation.” He supported a cap on welfare and letting states determine eligibility. In other words, a Dole presidency was all in for state feudalism, leaving the feds with little to do except write big checks. No way he was letting Clinton make a move to his right.

But the presidential challenger went farther. Reverting to his trademarked nastiness, Dole also accused Democrats of frightening older Americans about Medicare cuts.

Two hours later, Clinton spoke, attempting to sound conciliatory without completely capitulating. Willing to give “fast track” waivers to states meeting his basic reform criteria, he nevertheless defended a national approach to welfare and attacked conservative proposals as “a mask for budget cutting.” That said, he did agree with Dole about a “partnership” with states. Not to be outflanked, Dole had called them “laboratories for democracy” while literally begging governors to let Congress “move in your direction.” He managed somehow to sound angry and sycophantic at the same time.

By then, Burlington had become another kind of laboratory, a site to test whether people can live in a police state and still believe it’s democracy. Spoiler: it’s possible. The governors spoke incessantly about listening to the people, yet they were virtually inaccessible. If you weren’t wearing a badge — in other words, unless you were invited —you couldn’t get near them. Even surrounded by guards, Clinton had more spontaneous exchanges with the public during a brief downtown tour.

As Michael Moore put it, the only people these guys were close to were their bodyguards.

|

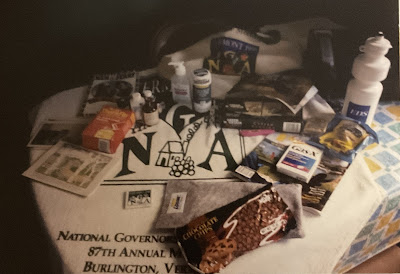

| NGA swag: from Gas-X to beach towels |

There was brave talk that weekend about local solutions; in Thompson’s words, “the most radical shift in government power since the Depression.” Yet the people making the claim were a bunch of entitled, middle-aged white men, many wannabes who wanted to join the federal cabal that they accused of enslaving their states.

Although anti-Contract protests were hard to avoid, they were never mentioned during the official proceedings. When Dean did finally acknowledge the opposition at a press briefing, it was to go on the attack. His target: a few protesters who had sprayed irreverent slogans that greeted the governors on their way to Sunday brunch. By making communication between officials and critics impossible, however, the NGA had prodded them toward more attention-getting tactics, then ignored or discredited the response.

At one point C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb asked Boston Globe writer Peter Gosselin about the impact of protesters. “They’re not being heard,” he admitted, “because the governors think they’re grappling with radical ideas.”

What ideas? Work requirements, limiting the duration of welfare payments, requiring underage mothers to stay at home (a Clinton waiter criteria), government-business partnership, extra money for high growth states, and the “one size doesn’t fit all” mantra. Ranging from old hat to opportunistic, none of those ideas were new. But one radical idea did emerge: a suggestion that individual entitlement might be replaced by state entitlement. The implication was that, although welfare and other safety net programs might become privileges, states are entitled to open-ended welfare checks. And governors should have the right to spend the money as they see fit.

None of this was directly discussed in public, and certainly not with anyone lacking a badge. Instead, in his first briefing as the new NGA chair, Thompson offered some official spin. “We’re moving from paternalism to partnership,” he proclaimed, a handy euphemism for a profound shift in the relationship between states and the federal government. But this was a partnership between only elected officials, and clearly did not include the public.

Gov. Roy Romer, a Colorado Democrat, was somewhat more candid about what had transpired. He labeled the annual meeting an exercise in “train wreck avoidance.” By one definition, a wreck might have been any confrontation that derailed the move toward block grants. But an actual wreck had already occured. Debate over welfare was diverted to hot button issues, a long-honored national commitment to helping the poor had been undercut, and more people would ultimately pay the price. During his re-election campaign, Clinton called it “ending welfare as we know it.”

Less than two months later, governors got most of what they had requested behind closed doors in Burlington: it came as a Senate welfare bill giving states broad control over cash and childcare programs. Federal aid to the poor would no longer be guaranteed, welfare benefits would be limited to five years, and half of all recipients would have to be working by 2000. Only 11 Democrats and one Republican voted no. The House version went even farther.

President Clinton praised the result and Bob Dole called it “a revolutionary step in the right direction.” Two decades later, when he ran against Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders called it “scapegoating people who were helpless.”

Greg Guma is the author of “The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution,” “Dons of Time,” “Uneasy Empire,” and “Spirits of Desire.” His latest book is “Restless Spirits & Popular Movements: A Vermont History.”

No comments:

Post a Comment