On Writing Restless Spirits & Popular Movements

I’ll start with a confession. I wasn’t born in Vermont. In fact, more than 50 years ago, when I first moved to the state as a 21-year-old refugee from New York, people like me were often stuck with an unflattering label — flatlander. It made a difference then — not to be born in the Green Mountains. Not to be a “real Vermonter.” That’s one of many things that have changed.

I did marry a Vermonter, which helped a bit. And in my first five years, living in southern Vermont, I was lucky to get three illuminating, educational jobs — daily newspaper reporter and photographer, publications director at Bennington College, and local manager of work and training programs for the Dept. of Labor, which involved finding jobs and counseling for at-risk teens and unemployed adults. Taken together, these jobs provided a practical education in real Vermont life.In a way, that’s when the seeds of this book were first planted. Here’s just a little bit from a chapter about — among other things — what I witnessed as a reporter:

“…in December 1968, Richard Nixon was back in Washington selecting his cabinet. Vietnam peace talks were stalled in Paris and the Defense Department called up another 33,000 young men to fight the war, bringing the total to half a million troops. My beats in Southern Vermont were far less momentous — district court, local schools, and the Village Trustees.

“One night editor (Tyler) Resch accompanied me to a school board meeting, drew a diagram identifying the people around the table, and then left. Now it would be sink or swim. In the grand scheme of things the story mattered little. But for the Banner’s readers, it did mean something. Without a local TV station, and long before the internet, my report was their main way to understand what was happening in the school system. If I couldn’t explain it I had no business calling myself a reporter.

“As luck would have it, a political storm was brewing. Mt. Anthony Union High School, built in the blush of a progressive educational era, was also at the center of Bennington's pain. Its alma mater, "The Impossible Dream," turned out to be prophetic. An idealistic plan for local education was about to be derailed by a cultural backlash.

“After the school superintendent resigned a dispute had developed over who would replace him as acting chief. The elementary school board wanted Assistant Superintendent George Sleeman. The supervisory union, which combined both the elementary and high school boards, was not so sure. On the surface it looked like a minor bureaucratic fracas, a question of who could sign checks until a permanent chief was selected. But it was actually part of a long-running conflict over the fundamental direction of education and community life.”

There’s much more to that story in the book, my first face-to-face encounter with culture war.

|

| Culture war at Mt. Anthony Union High School, 1969 |

After those critical first years, I moved north, got a masters degree at UVM, started a used bookstore with some friends— we called ourselves the Frayed Page Collective, helped organize alternative events and the local anti-nuclear movement, and, as many people were celebrating the US bicentennial, put together an unusual publication that told Vermont’s story from a different perspective. We named it Vermont’s Untold History. It reinterpreted events from a radical, class conscious perspective, and collected anecdotes and oral history about labor and women’s struggles. I’ve been adding material and improving on that start ever since.

At times I was a journalist and editor, for the Vanguard Press, Toward Freedom and Vermont Guardian, among others; at other points I was an activist — and sometimes even a political candidate. At times I left the state, for jobs in New Mexico and California, and later to become CEO of the Pacifica Radio network. But I always returned to Vermont —and eventually, a decade ago, to journalism with VTDigger, then a new online news outlet. In recent years there have been talks at the University of Vermont and the Vermont Historical Society, interviews with assorted journalists during Bernie Sanders’ two presidential campaigns, several books, an exhibit on the 1960s at the Bennington Museum. But Vermont’s history was always on my mind, and eventually that enduring interest led to Restless Spirits & Popular Movements.

I don’t claim it is a comprehensive history of the state. But it does revisit many of the key moments, hopefully provides some fresh perspectives, and also reintroduces some of the individuals and movements that have been forgotten or overlooked in the past. As I note in the introduction, there’s an old saying — History is written by the victors. In Vermont, for more than a century, that meant Republicans. From 1860 — when Abraham Lincoln was elected president — to 1962 — when Phil Hoff became Vermont’s first modern era Democratic governor — every US congressman, senator and governor was a Republican. Not even Franklin Roosevelt could win here. And this also meant the state’s history was seen through a decidedly Republican lens. That’s another thing that has changed.

As I said, this history looks at the past in terms of movements and many of the people who played crucial roles. People like Matthew Lyon, who arrived in Vermont in bondage, became a fighter in the Revolutionary War, represented the state in the US House of Representatives, defied President John Adams, and, as a result, was imprisoned in Vergennes under the notorious Sedition Act, which made it a crime to criticize the government or president. Lyon was re-elected anyway — while he was still in jail. And in 1800 he cast a crucial vote for Thomas Jefferson, making Adams our first one-term president.

In the early 1800s, a time marked by movements against slavery, aristocracy, drunkenness and wage labor, other leaders emerged, men and women who questioned authority and conventional wisdom. For example, I share stories about…

* John Humphrey Noyes, a Putney native who was forced to flee the state because of his controversial religious views and start the utopian Oneida Community in upstate New York

* Willian Miller, who launched a millennial cult that thought the world would end in 1844. When it didn’t, he changed the date. Thousands doubled down and stuck with him

* Thaddeus Stevens, a Danville native who made his name in Pennsylvania where he emerged as a leading abolitionist and helped found the Republican Party

* Clarina Nichols, an early feminist who successfully pushed through some of the state’s first legislation that expanded the rights of women — more than 70 years before women won the right to vote

* and Willian Palmer, a Jeffersonian and former judge who served several terms as an anti-Mason governor. He was part of a larger movement that believed Masons were an anti-democratic secret society. The movement lasted only a decade, but it introduced political innovations like nominating conventions and party platforms. It also sparked a state constitutional crisis that led to the creation of Vermont’s State Senate.

In the early days, by the way, some of these amazing Vermonters — Lyon, Noyes, Stevens and Clarina Nichols among them — ultimately felt they needed to leave the state to pursue their ideals and dreams. By the mid-19th century, sheep outnumbered people by six to one, and it wasn’t unusual to hear locals say, “The only place that’s growing is the cemetery.”

As already mentioned, Vermont was basically a one-party state for a century. But Republicans ranged from railroad and Marble tycoons to progressives like Ernest Gibson, who struggled to expand the state’s role in protecting public welfare in the 1940s. And in Burlington, James Burke, an Irish Catholic blacksmith, was elected mayor seven times between 1903 and 1933. More than half a century before the rise of Bernie Sanders, Burke led the Democratic Party as it instituted progressive reforms — things like a public dock and public power, a train depot, and playgrounds for children. He also led a fusion movement that challenged the Republican’s monopoly of power. There is an extensive chapter, and much new research, about what I call The Age of Burke. A local magazine, 05401, recently published part of it.

|

| James Burke, 1906 |

Here is another excerpt, this one about the early contributions of African Americans and the state’s response to racism. Although Vermont’s Constitution had outlawed most forms of slavery and Vermont submitted so many anti-slavery petitions that the Georgia legislature instructed its governor to “transmit the Vermont resolutions to the deep, dank and fetid sink of social and political iniquity from whence they emanated,” the response was far from unanimous, then or later. From the book:

“Until recently, the impact of African Americans on Vermont’s reputation for innovation and independent thinking has been greatly underrated. Among the early Black leaders were Lucy Terry Prince, a former slave who resettled in Guilford and became the first African American poet in the United States; Lemuel Haynes, a minister in Rutland and first African American ordained by a U.S. religious denomination; and Alexander Twilight, the first Black person to serve in any state legislature.

Twilight was a teacher, but also designed Athenian Hall, a school and dormitory that became the home of the Orleans Historical Society. In 1836, a crucial transition period in Vermont, Twilight fought to reform education funding in the Legislature. Vermont’s record in the struggle to end slavery is certainly laudable, and features a broad range of leaders and strategies. Yet when William John Anderson Jr. became the second black elected to the state legislature in 1945 — more than a century after Twilight's time — he still could not enter the Montpelier Tavern and Pavilion Hotel.

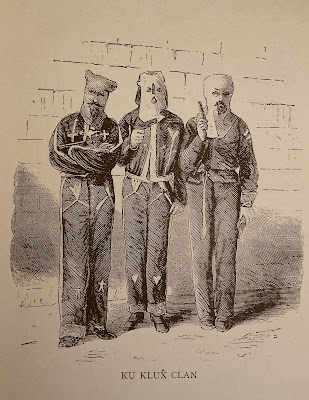

In the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan saw a brief revival in Vermont. There were cross burnings and rallies, but also acts of courageous resistance. In order to go after the KKK’s secrecy, Burlington passed an ordinance against wearing masks. Rutland residents responded by staging a boycott of any business owner who dared admit to Klan membership. Frequent condemnation by local newspapers also made a difference.

On the other hand, Kake Walk, a minstrel show performed in blackface, continued at UVM fraternities until 1969. When confronted, UVM President Lyman Rowell was defiant, refusing to “remake the university” for the benefit of Black people. The student senate eventually ended the tradition….

Historian John Meyers says “the militant wing of the antislavery movement regarded slaveholding as sinful and saw organization and agitation as necessary to gain adherents and promise hope for destroying the institution.” Perhaps the most profound expression of this view was Vermont’s Underground Railroad.”

Vermont has often struggled against the tide. It used to be known as the “Reluctant Republic,” a reference to the decision — by those who controlled the region during its early development — to remain an independent republic for 14 years after the Declaration of Independence. Even after it joined, its relationship with the United States remained tentative for decades.

The maverick spirit persisted. In the 1930s, for example, when unemployment was high and public works were a major response to the Depression, it resisted pressure to build a 250 mile highway along the spine of the Green Mountains. Known as the Green Mountain Parkway, the road was supposed to bring Vermont into the modern age. Supporters, including most of the establishment, called it a progressive idea. All that was needed was a small financial commitment by the state legislature. But it became a very hot potato, and the legislature decided in 1936 to pass the decision on the local communities in town meeting votes.

As I explain, “In the end a convincing majority rejected the federal government’s $18 million offer. There was strong support for the road in northern counties — Chittenden, Franklin, Grand Isle, Lamoille, and Washington — but it was roundly rejected in the south. As some opponents put it, they simply didn’t want the national government to become a large property owner and regulator of land in Vermont. The final count was 31,101 in favor to 43,176 opposed.

“Was the decision enlightened or selfish, provincial or progressive, conservative or radical? It is difficult to categorize. Nevertheless, Vermonters had used their unique form of grassroots democracy — town meeting.”

****

The definition of progressive has evolved over the years. “No going backward,” said Mayor James Burke in the early 20th century. For George Aiken and Ernest Gibson, in the 1930s and 40s, it meant challenging their own party’s orthodoxy. For Governor Phil Hoff, in the 60s, it meant fairness and equality, growth and good government. I also tell their stories in the book.

And then came Bernie Sanders. Here’s an excerpt about how Burlington’s modern progressive movement began:

“In January 1981, (Gordon) Paquette won a caucus fight for a fifth term. But afterward Richard Bove, owner of a popular local Italian restaurant, left the Democratic Party to run as an independent. Republican Party leaders decided not to oppose him and banked on his re-election. As a result, his main opponent became Bernie Sanders, the former third party radical now running as an Independent.

Sanders opposed Paquette’s proposed 10 percent increase in property taxes and promised to work for tax reform. The recently formed Citizens Party, which had backed environmentalist Barry Commoner in the 1980 presidential election, ran three candidates for the City Council, also known as the Board of Aldermen. The incumbents tried to ignore them, assuming that a group of activists had no chance of upsetting the status quo. But Sanders was hard to ignore, and local leaders of both major parties underestimated the growing influence of neighborhood groups, housing and anti-redevelopment activists, young people, the disenfranchised elderly, and the city’s countercultural newcomers. They also shrugged off the possibility that some of Paquette’s supporters might want to send him a message.

By the time Sanders and the mayor faced each other over a folding table at the Unitarian Church tempers were hot. Sanders exploited local anger by linking the mayor with Antonio Pomerleau, then a dominant figure in Vermont shopping center development, who was leading efforts to turn Burlington’s largely vacant waterfront into a site for commercial and condominium development.

“I’m not with the big money men” Paquette protested. Frustrated and desperate, he warned that if Sanders became mayor Burlington would become like Brooklyn. He looked honestly shocked when people hissed at him.

The race began as a long shot, but Sanders turned his shoestring campaign into a serious challenge. Nevertheless, on Election Day Paquette and the Democratic old guard still predicted a decisive victory. After all, Reagan had been elected President only four months before. Sanders was no threat, they assumed, nothing more than an upstart leftist with a gift for attracting media attention.

“It’s time for a change. Real change.” That was his slogan. Bernie wanted open government, he said, and new development priorities. He opposed the upscale Waterfront project and Interstate access road to downtown. He supported Rent Control.

“Burlington is not for sale,” he said. “I am extremely concerned about the current trend of urban development. If present trends continue, the city of Burlington will be converted into an area in which only the wealthy and upper-middle class will be able to afford to live.”

On March 3, 1981, with a few thousand dollars, a handful of volunteers and a vague reform agenda, Sanders won the mayoral race by just ten votes. Burlington had a “radical” mayor, a self-described socialist who was determined to change the course of Vermont history. Terry Bouricius, a Citizens Party candidate for the City Council, became the first member of that party elected anywhere in the country. In an odd twist, Bouricius won in Ward Two, the same place that had given Paquette his first term on the City Council 23 years earlier.

According to Gene Bergman, then an activist with the low-income advocacy group PACT, and later a Progressive city councilman and assistant city attorney, the victories would be “just the beginning of the efforts to bring the long neglected and exploited working class to its rightful place in the city.” The next three decades proved just how much the political establishment underestimated Sanders’ appeal, not to mention the potential for a progressive movement in the city and beyond.

Burlington’s progressives not only consolidated their local base, affecting many aspects of city management and shaping the local debate. They challenged the accepted relationship between communities and the state, and fueled a statewide progressive surge. They also weathered the storms of succession struggle, demonstrating with Peter Clavelle’s 1989 mayoral victory on the Progressive ticket that — in Bernie’s words — “It’s not just a one-man show, it’s a movement.”

Beyond profiling individuals and exploring political and social movements, this history also attempts to define a set of evolving values, an elusive mix that makes up what many have called The Vermont Way. What are they?

* Political values — Accountability, Autonomy, Local Control, Citizen Government

* Ecological values — Conservation, Balance, Human Scale

* and Social values — Tolerance, Solidarity, and Dissent

They’ve mattered in the past, and still matter today. But as I also write, “Vermont is not some bucolic refuge, a New England Shangri-La without flaws, blind spots and dark corners.

“Along with its virtues and achievements, it has at times practiced the provincial politics of exclusion, delay, and judging books by their covers. Case in point: A century after the women’s suffrage movement, Vermont politics remains largely a white men’s club. The three-member Congressional delegation is all male — and always has been. No woman has ever represented Vermont in Washington. And only one has been governor.”

But that situation seems about to change.

So, what is the Vermont Way? I don’t claim to have a complete definition. Some believe it’s the ability to create something out of nothing.

When he left the Republican Party in 2001, US Senator James Jeffords said, “Independence is the Vermont Way.” And Consuelo Northrup Bailey, a native Vermonter who in 1955, became the first female lieutenant governor in the nation, remarked in her autobiography that the character of Vermont was defined by “everyday, common, honest people who unknowingly salted down the Vermont way of life with a flavor peculiar only to the Green Mountains.”

Those are just three definitions. In a concluding chapter, I provide one more:

“Based on Vermont’s unusual history and remarkable leaders, it looks like a delicate dance of sovereignty and solidarity, independence and mutual aid, or as the motto adopted as part of Vermont’s Great Seal in 1788 says, “Freedom and Unity.”

“It has evolved and adapted when necessary. Frequently a laboratory for autonomy, citizen government and local democracy, Vermont has become a mixture of pragmatism and idealism, tolerant, concerned and yet sometimes wary of newcomers or higher authorities, and naturally drawn to solutions that stress conservation and balance, civil liberties and human scale.”

July 2022 Talk at Sandy’s Bookstore and Bakery in Rochester, Vermont.