It’s a disturbing pattern: blaming newcomers, immigrants and those who are different for our problems and turning deep disagreements and dissent into crimes. It has happened often around the world in times of war and domestic division.

In the US, it happened shortly after the colonies declared their independence from Great Britain and established a new form of government. Again in the 1880s, when workers — many of them immigrants from Europe — were demanding better working conditions from big business. And after the two world wars, when ideas that challenged capitalism were considered so threatening that thousands were arrested, jailed, and deported.

We’re hearing it again now. We’re in a war, say politicians and officials who run federal agencies and state governments. But not an invasion from another nation. Instead, it’s a homegrown threat from so-called “alien criminals.” That’s the rationale for the US president’s use of an 18th century law — the Alien Enemies Act — that supposedly allows the federal government to detain and deport people who immigrate from countries deemed foreign adversaries. It’s part of a sweeping crackdown that might someday target anyone.

One small victory in this struggle was a Vermont judge’s ruling on April 30 to release Mahsen Madhawi, a Palestinian Vermonter detained in April by federal immigration authorities. A student organizer at Columbia University and lawful US resident for a decade, he was arrested in Colchester, Vermont during an interview as part of his citizenship naturalization process. US District Judge Geoffrey Crawford mentioned the Red Scare and McCarthy era in his decision, periods he compared to the present. “These are not chapters that we look back on with much pride,” he said.

The Alien Enemies Act is part of the Alien and Sedition Acts, adopted in 1798, which gave the federal government expanded authority to regulate non-citizens in times of war. Since then it has been used three times, during the War of 1812 and both World Wars I and II. It can be invoked “whenever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion” and allows for non-U.S. citizens aged 14 and older to be “apprehended, restrained, secured and removed as alien enemies.”

The Supreme Court is currently considering whether this applies to those rendered to prison in El Salvador or elsewhere. Meanwhile, Fernandez Rodriquez, a Southern District of Texas judge appointed by President Trump, has prohibited the administration from using the Act because the president’s claims about a Venezuelan gang do not add up to an “invasion.”

The original excuse for this abuse of power was French interference with American shipping more than 200 years ago. It was supposed to allow President John Adams to imprison or deport any potentially dangerous alien and declare the publication of “false, scandalous or malicious writing” against the law. But the first target was an American, an opposition newspaper editor. Others jailed included a Vermont congressman who was re-elected anyway. Adams’ successor Thomas Jefferson pardoned everyone who was convicted and even refunded the fines.

A related law, the Espionage Act, was passed in 1917, and became a weapon to imprison people who opposed World War I, conscription or other policies. That included Eugene Debs, a socialist candidate for president who was jailed for interfering with the draft. By the end of 1919, after the war had ended, hundreds of Russian immigrants were nevertheless deported; hundreds more were rounded up and subjected to secret hearings.

During the Second World War, 120,000 US citizens of Japanese ancestry were taken from their homes and imprisoned in remote detention centers, simply because they were suspected of potential disloyalty. After the war, dissent was risky when relations with Russia hardened into the Cold War. An anti-sedition law, the Smith Act, passed in 1946, was used against leaders of the Socialist Workers Party, then against those suspected of Communist sympathies. Few people had enough nerve to defend the first victims, and the war on dissent escalated. Repression soon snowballed into another red scare, leading to state and federal investigations of “un-American activities.”

In 1951, a Supreme Court decision approved the imprisonment of 11 Communist leaders, not for any overt acts that threatened national security, but rather simply for organizing a political party and teaching Marxism. We are fast approaching a similar legal turning point.

But let’s focus on an earlier example, the red scare known as Haymarket, a crackdown launched in early May 1886 that set back the labor movement and etched the image of “foreign radicals” as terrorists into the American psyche. It began in Chicago, then experiencing rapid industrialization and massive immigration. Irish, Scandinavian, Czech, English and German newcomers dominated the blue-collar workforce. First and second generation German immigrants comprised 33 percent of the city’s population, a larger number than those living in most urban centers in Germany.

Strikes and peaceful demonstrations were often disrupted by armed police, who beat and sometimes killed protesters. Businesses created private armies, and newspapers called for a crackdown. Similar to the current rhetoric, those who opposed government policies or business practices were labeled violent outsiders. A few protesters did indeed support an armed response to official repression.

The confrontation between the labor movement and capitalists crescendoed on May 1, the first May Day, when 300,000 workers across the country participated in a walk out and demanded a shorter work week. This launched the movement for an eight-hour day. In Chicago, 40,000 people went on strike. Two days later, during a confrontation between strikers, scabs and management thugs, several people were killed.

The following night, May 4, someone threw a bomb into the crowd during a protest, killing several policemen. It was just the excuse the establishment needed. What followed was one of the most shameful moments in US legal history.

The first step was a reign of terror: offices, meeting halls, and private homes raided; dozens arrested, interrogated, and beaten; some newspapers shut down while others ran hateful headlines and propaganda. Eventually, eight men were arrested, all but one of them immigrants. None could be directly linked to violence or the bomb, but that didn’t matter. They were essentially placed on trial for their “unpopular” views.

Guilty verdicts were predictable. Nevertheless, over the next year a strong clemency campaign was waged. Although many supporters did not endorse the admittedly radical views of those who had been condemned, they knew that a death sentence was deeply unjust. And public sentiment did shift. This eventually seemed to persuade the governor, but he was also swayed by business leaders demanding executions. In the end he commuted the sentences of two defendants who wrote letters expressing remorse — basically admitting to a crime they had not committed. One of those convicted opted for suicide the day before the executions; four men were hung.

The impact was broad and profound. It demonstrated how the government and business can join forces to repress and destroy those — especially immigrants — whose beliefs and lifestyles threaten them. But for decades the Chicago martyrs were also a symbol for workers and activists around the world, their dignity in the face of ignorance and repression inspiring countless others to stand up. The hangings had underlined the fragility of democracy in a time of fanatical behavior and manipulation of mass opinion.

At times, the moment we are in sounds like a strange echo of the struggle between bible fundamentalists and believers in evolution early in the 20th century. In the moving play, Inherit the Wind, a fictionalized defense attorney, Henry Drummond, rails against the forces set loose by what became known as the Scopes Monkey Trial. “Can't you understand?” he implores the judge, “that if you take a law like evolution and you make it a crime to teach it in the public schools, tomorrow you can make it a crime to teach it in the private schools? And tomorrow you may make it a crime to read about it. And soon you may ban books and newspapers. And then you may turn Catholic against Protestant, and Protestant against Protestant, and try to foist your own religion upon the mind of man.

“If you can do one, you can do the other. Because fanaticism and ignorance is forever busy, and needs feeding. And soon, your Honor, with banners flying and with drums beating we'll be marching backward, backward, through the glorious ages of that Sixteenth Century when bigots burned the man who dared bring enlightenment and intelligence to the human mind!”

Also available at Center for Global Research: https://www.globalresearch.ca/immigrants-enemies-when-dissent-crime/5885834

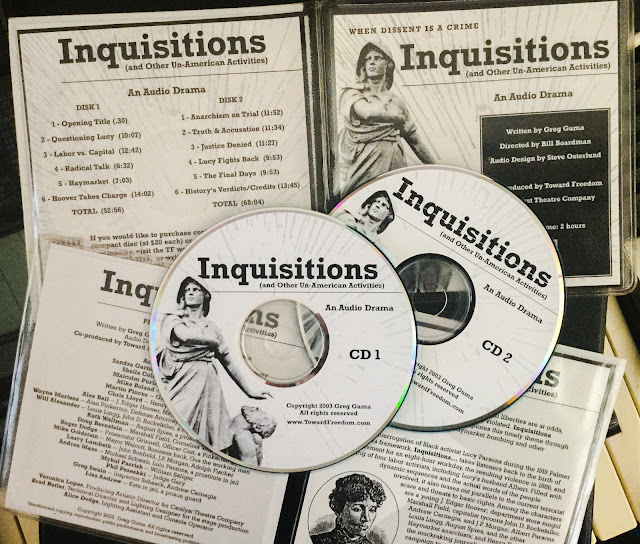

If you want to learn more about Haymarket and repression of dissent, listen to my play Inquisitions (and Other Un-American Activities), now available as a podcast series:

Spreaker:https://facebook.spreaker.com/episode/inquisitions-an-audio-drama-act-1--19064693

Distributed by Squeaky Wheel: https://www.squeakywheel.net/inquisitions.html

Inquisitions — An Audio Drama in Three Acts

When national security and civil liberties are at odds, fundamental rights are often undermined or violated. “Inquisitions (and Other Un-American Activities)” explores this theme through a dramatic recreation of the Haymarket bombing in Chicago and other crackdowns on dissent. With the FBI interrogation of activist Lucy Parsons in 1919 by a young J. Edgar Hoover at its center, the drama takes listeners back to the birth of the movement for an eight-hour workday, the resulting violence in 1886 Chicago, and the trial and execution of innocent immigrant activists. Written by Greg Guma, directed by Bill Boardman, and produced by Catalyst Theatre.

No comments:

Post a Comment