James Burke’s allies considered him honest and fearless, driven by high ideals of civic pride and duty. His political enemies questioned his motives and called him a demagogue. He sometimes called them “corporate interests” or “foreign capitalists.”

He was no friend of Elias Lyman’s coal company, for example, or of the Masons and the railroads. And in his 1904 race for mayor, he forced the Republic candidate, Rufus Brown, to publicly deny that his campaign was secretly financed by Burlington Gas Light.

One of the most difficult crusades of Burlington’s early progressive era put him at odds with both the Central Vermont and Rutland Railroads over public ownership of waterfront land. The railroads had owned and controlled the water’s edge since Burlington emerged as a commercial center, and weren’t willing to let the city take any part of the land for a “public wharf.”

That was precisely what Burke proposed to do.

The first breakthrough came in 1902. In December, only days after the city won a legislative go-ahead for the light plant – what eventually became the Burlington Electric Department – it also received approval to operate a “public wharf…for the landing, loading and unloading of boats and vessels.” Plus, the city would be permitted to take land by eminent domain. By 1905 Burke was confident that Burlington would have a wharf within a few months.

But months ended up stretching into years.

The railroads were refusing to sell the city any land, so Burke hunted down some frontage at the foot of Maple Street that had, as he put it, “escaped the eyes of corporate greed.” Most land in that area was owned by the Rutland line. In June 1905, as the city sought construction bids, the railroad won a court order to block construction. Filling in the slip would destroy its “property right,” the company argued.

The court battle dragged on into the next mayoral election. The Burlington Free Press, whose staff member Bigelow frequently ran against Burke, urged the city to negotiate with the other railroad, Central Vermont, for a lease while simultaneously accusing the mayor of trying to “make political capital” out of the issue.

Burke won anyway, by 140 votes, mainly based on his popularity in waterfront neighborhoods. In his fourth annual message, he charged that, “The citizens of Burlington are getting impatient over this question (the wharf)…An outraged people will hold us responsible if we show any inclination of shirk our duty in this great battle now going on with corporate interests which are ever vigilant and successful in watching after their own interests.”

Despite public opinion or impassioned speeches, Central Vermont aggressively opposed the city’s public wharf plans for several years in a variety of legal actions, including a 1909 Supreme Court case.

Like the private utilities, the railroads wanted to establish that Burlington had no legal right to run a public business that would “enter into competition with the world at large.” The state’s top judges disagreed. Vermont government could “build or aid others in building, wharves for public use and in aid of trade and commerce; and it is equally clear that whatever the state can do in this behalf, it can delegate to a municipality to do.” It could be almost anything of special local benefit, anything considered “proper means for promoting the prosperity of its people.”

The decision was handed down on January 16, 1909, less than two months before Burke returned to City Hall after defeats in 1907 and 1908. James Tracy, who thought Burke tactless and possibly a dangerous demagogue, had to concede in a Vermonter Magazine profile that his persistence and success on the wharf issue had netted him “prestige among the common people who look upon him as a safe leader and wise counselor.”

The negotiation nevertheless dragged on. The economic establishment apparently hoped to win by wearing down the opposition and exploiting technicalities. By 1910 Burlington was under legal attack by the railroads, Burlington Light and Power, and the Masons. And before all the disputes could be resolved, Burke – the politician at the center of the storm – was out of office again. Burke’s old rival Robert Roberts had returned to electoral politics after a ten-year absence to defeat the mayor in five of the city’s six recently-redrawn wards.

But comebacks were Burke’s forte. In 1913 he made yet another one, and immediately picked up his discussions with the railroads. Now the mayor linked the purchase of wharf property with plans for a Union Passenger Station nearby. The Public Service Commission was invited into the debate, and the Supreme Court ironed out the details. Both Central Vermont and the Rutland Railroad eventually accepted the city’s proposal.

In 1915 the city purchased 160 feet of lakefront property near College Street for $8,000. A decade-long battle with corporate power had been won.

We can't just buy, build or bully our way out of problems. But we do have another choice: learn from the past, open up the debate, and build a movement for preservation & change.

Monday, December 21, 2015

Saturday, December 19, 2015

Burlington in the Age of Burke

For these Burlington stories, let’s start in September 1902, ten years before Teddy Roosevelt’s famous 1912 visit to Barre. The President had been to the Queen City a year earlier. That day he was riding with Percival Clement on his railroad after a visit with Vermont Lieutenant Governor Nelson Fisk at Isle LaMotte. Then word came through that President McKinley had been shot by what the papers were calling a “crazed anarchist.”

Now, a year later, Roosevelt – ridiculed as a “wild man,” that “damned cowboy” hated by Wall Street, Vice President under McKinley for less than a year – triumphantly returned to Burlington as President.

Clement was about to play a strange and convoluted role in Vermont’s progressive history. Decades before his stiff resistance to womens’ suffrage he was part of a progressive fusion movement that attempted to overthrow the Proctor Republicans. He was also a railroad tycoon, owner of the Rutland Herald, and friend of Teddy Roosevelt.

In 1902 Mayor Donley C. Hawley stood with the new president at the train barn near the waterfront, surrounded by flags and bunting. Roosevelt told the Vermonters, “You have always kept true to the old America ideals – the ideals of individual initiative, of self-help, of rugged independence, of the desire to work and willingness, if need, to fight.”

The truth is, Republicans like Hawley were actually suspicious of “their” president. His rhetoric about a “square deal” for working people and control of big business sounded, well…. radical. But Democrats like James Burke were unabashed admirers. Burke was an Irish Catholic blacksmith and a leading spokesman for the city’s growing Democratic Party. He had been an alderman and run unsuccessfully for mayor in 1900 and 1902. Now he was part of a statewide fusion movement with dissident Republicans. Like Roosevelt, he projected himself as a pragmatic reformer, thriving on idealism, moral outrage and an ability to inspire the masses.

.

March 3, 1903. The hotly contested mayoral race between Burke and Hawley drew an overflow crowd to the city clerk’s office that night. The men in the room – remember, only men could vote – perched on windowsills or stood on the rail that surrounded the aldermanic table. As the results for various wards were announced the winning side cheered. Hawley, who was a surgeon, came out of top in the affluent areas. But Burke’s persistence was finally paying off in the inner-city, immigrant wards. And he had two compelling issues: a proposed city-owned light plant and local licensing of saloons.

When the final votes were tallied, Hawley had a three-vote margin. But that was because City Clerk Charles Allen refused to count ballots marked twice. Burke was livid and took the matter to the Vermont Supreme Court – and won, gaining certification of an 11-vote victory by early summer.

It took more time, but he also got a light plant. Two years later, during his third one-year term, Burke’s daughter Loretta pressed a button at the bandstand in City Hall Park energizing two circuits of streetlights with power from the newly built plant.

Attempted Fusion

Burke’s political vision stretched beyond the borders of the city, and by 1906 he became further embroiled in an effort to wrest control of the governor’s office from the Republicans. To attempt it he forged a delicate personal alliance with Percival Clement.

The Burke-Clement alliance was largely rooted in political expediency. Both men wanted to be governor and knew that a Democrat could not win statewide. Both had also been mayors, Clement in Rutland, although his control of the Rutland Railroad didn’t ease negotiations about the Burlington waterfront, which was owned by Clement’s line and Central Vermont Railway. But there was also an ideological affinity that bridged the class barrier between them. Both were ardent supporters of the “local option” to issue saloon licenses and vocal critics of graft by marble and coal interests dominating the GOP.

In 1906, Roosevelt was on the attack against the beef, oil and tobacco trusts. In Vermont Clement was still warring with the Proctors, especially Fletcher Proctor, the Republican candidate for governor.

Burke had won another term as mayor over Walter Bigelow, the 40-year-old chairman of the state Republican Party and night editor at the Burlington Free Press. He saw a “bright and glorious future” for the city and wanted people to move beyond “a narrow or partisan point of view.” That was also part of the reason he was involved in the movement Clement was building.

At first it was called the “Bennington idea,” referring to the town where petitions first circulated for Clement to lead an independent movement that aimed to “save the state” after 50 years of Republican rule. But Clement’s supporters felt that a fusion with Democrats was essential, so 1906 they tried to induce Burke to join the ticket.

Burke wasn’t persuaded. Giving Clement the Democratic nomination would effectively put him in control of the party. If a Democrat won the presidency in 1908 Clement would get to hand out the patronage. The Democrats were still divided on June 28, the day both the Independent and Democratic state conventions were held in Burlington.

The Independents convened in City Hall. The Democrats met at the armory. Meanwhile a joint committee worked out an agreement to divide the state ticket. The Democrats would field candidates for half of the slate, Independents would fill the rest. After accepting the Independent nod Clement walked with Burke to the Strong Theater for a joint assembly.

The debate over fusion was heated. Some people accused Burke of opposing the idea because he couldn’t head the ticket. Eventually speaking for himself, Burke reminded the audience that he had backed fusion under Clement four years earlier. But the “local option” for alcohol was no longer a galvanizing issue and Clement was, after all, still basically a Republican.

The Democrats rejected Burke’s advice and approved a joint slate headed by Clement and Democrat C. Herbert Pape. With more than a thousand people packing the theater, Clement took center stage, Burke at his side, and launched into a long and fiery attack on the Republican machine, the marble companies, and the inefficiency and graft that was robbing the people.

Burke actively backed Clement’s war on the Proctor Republicans, spending much of his time that summer on the campaign trail attacking Republican graft and rule. As usual, his rhetoric was also rich with praise of Roosevelt, calling him “the greatest Republican since Lincoln and the greatest Democrat since Jefferson.”

“Reform is in the air,” he shouted from the back of Clement’s private train that fall, “and Vermont will share in the benefits that come from the general revolt being made against ring rule and graft.” Burke envisioned a popular coalition of Lincoln Republicans and Jefferson Democrats that would wipe out party lines. It might even combat corporate lobbying on labor issues like the nine-hour day and minimum wage.

But Fusion was defeated by Republicans united behind Proctor that November. And the following March, Burke came up short in his first mayoral race in five years – to Walter Bigelow. The defeat was devastating for political allies who lost their jobs and watched old opponents return to power. Twelve years later, in 1918, Clement did become governor – as a Republican.

NEXT: On the Waterfront

Now, a year later, Roosevelt – ridiculed as a “wild man,” that “damned cowboy” hated by Wall Street, Vice President under McKinley for less than a year – triumphantly returned to Burlington as President.

Clement was about to play a strange and convoluted role in Vermont’s progressive history. Decades before his stiff resistance to womens’ suffrage he was part of a progressive fusion movement that attempted to overthrow the Proctor Republicans. He was also a railroad tycoon, owner of the Rutland Herald, and friend of Teddy Roosevelt.

In 1902 Mayor Donley C. Hawley stood with the new president at the train barn near the waterfront, surrounded by flags and bunting. Roosevelt told the Vermonters, “You have always kept true to the old America ideals – the ideals of individual initiative, of self-help, of rugged independence, of the desire to work and willingness, if need, to fight.”

The truth is, Republicans like Hawley were actually suspicious of “their” president. His rhetoric about a “square deal” for working people and control of big business sounded, well…. radical. But Democrats like James Burke were unabashed admirers. Burke was an Irish Catholic blacksmith and a leading spokesman for the city’s growing Democratic Party. He had been an alderman and run unsuccessfully for mayor in 1900 and 1902. Now he was part of a statewide fusion movement with dissident Republicans. Like Roosevelt, he projected himself as a pragmatic reformer, thriving on idealism, moral outrage and an ability to inspire the masses.

.

March 3, 1903. The hotly contested mayoral race between Burke and Hawley drew an overflow crowd to the city clerk’s office that night. The men in the room – remember, only men could vote – perched on windowsills or stood on the rail that surrounded the aldermanic table. As the results for various wards were announced the winning side cheered. Hawley, who was a surgeon, came out of top in the affluent areas. But Burke’s persistence was finally paying off in the inner-city, immigrant wards. And he had two compelling issues: a proposed city-owned light plant and local licensing of saloons.

When the final votes were tallied, Hawley had a three-vote margin. But that was because City Clerk Charles Allen refused to count ballots marked twice. Burke was livid and took the matter to the Vermont Supreme Court – and won, gaining certification of an 11-vote victory by early summer.

It took more time, but he also got a light plant. Two years later, during his third one-year term, Burke’s daughter Loretta pressed a button at the bandstand in City Hall Park energizing two circuits of streetlights with power from the newly built plant.

Attempted Fusion

Burke’s political vision stretched beyond the borders of the city, and by 1906 he became further embroiled in an effort to wrest control of the governor’s office from the Republicans. To attempt it he forged a delicate personal alliance with Percival Clement.

|

| Percival Clement |

In 1906, Roosevelt was on the attack against the beef, oil and tobacco trusts. In Vermont Clement was still warring with the Proctors, especially Fletcher Proctor, the Republican candidate for governor.

Burke had won another term as mayor over Walter Bigelow, the 40-year-old chairman of the state Republican Party and night editor at the Burlington Free Press. He saw a “bright and glorious future” for the city and wanted people to move beyond “a narrow or partisan point of view.” That was also part of the reason he was involved in the movement Clement was building.

At first it was called the “Bennington idea,” referring to the town where petitions first circulated for Clement to lead an independent movement that aimed to “save the state” after 50 years of Republican rule. But Clement’s supporters felt that a fusion with Democrats was essential, so 1906 they tried to induce Burke to join the ticket.

Burke wasn’t persuaded. Giving Clement the Democratic nomination would effectively put him in control of the party. If a Democrat won the presidency in 1908 Clement would get to hand out the patronage. The Democrats were still divided on June 28, the day both the Independent and Democratic state conventions were held in Burlington.

The Independents convened in City Hall. The Democrats met at the armory. Meanwhile a joint committee worked out an agreement to divide the state ticket. The Democrats would field candidates for half of the slate, Independents would fill the rest. After accepting the Independent nod Clement walked with Burke to the Strong Theater for a joint assembly.

The debate over fusion was heated. Some people accused Burke of opposing the idea because he couldn’t head the ticket. Eventually speaking for himself, Burke reminded the audience that he had backed fusion under Clement four years earlier. But the “local option” for alcohol was no longer a galvanizing issue and Clement was, after all, still basically a Republican.

The Democrats rejected Burke’s advice and approved a joint slate headed by Clement and Democrat C. Herbert Pape. With more than a thousand people packing the theater, Clement took center stage, Burke at his side, and launched into a long and fiery attack on the Republican machine, the marble companies, and the inefficiency and graft that was robbing the people.

Burke actively backed Clement’s war on the Proctor Republicans, spending much of his time that summer on the campaign trail attacking Republican graft and rule. As usual, his rhetoric was also rich with praise of Roosevelt, calling him “the greatest Republican since Lincoln and the greatest Democrat since Jefferson.”

“Reform is in the air,” he shouted from the back of Clement’s private train that fall, “and Vermont will share in the benefits that come from the general revolt being made against ring rule and graft.” Burke envisioned a popular coalition of Lincoln Republicans and Jefferson Democrats that would wipe out party lines. It might even combat corporate lobbying on labor issues like the nine-hour day and minimum wage.

But Fusion was defeated by Republicans united behind Proctor that November. And the following March, Burke came up short in his first mayoral race in five years – to Walter Bigelow. The defeat was devastating for political allies who lost their jobs and watched old opponents return to power. Twelve years later, in 1918, Clement did become governor – as a Republican.

NEXT: On the Waterfront

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Progressive Movements and The Vermont Way

In conjunction with a recreation of Teddy Roosevelt’s 1912 visit to Vermont during his Progressive Party run for president, in 2012 writer and historian Greg Guma presented stories and thoughts at the Vermont History Center about the evolving nature of progressive politics in Vermont.

The journey includes vignettes and impressions on how the Anti-Masons briefly took the state, why feminist Clarina Nichols decided to leave, Burlington’s early progressive mayor James Burke and a 1906 fusion alliance that almost overturned the Proctors, progressive Republicans in the 1940s and Phil Hoff’s 60s breakthrough, the Green Mountain Parkway fight, a Vermont conservative who stood up to McCarthy, and the rise of Bernie Sanders.

Elizabeth Dwyer, the inimitable editorial page editor of the Bennington Banner, used to talk about erecting a toll road at the border with upstate New York. Flatlanders were finding it way too easy to get in. It wouldn’t hurt to discourage them a bit.

Liz was not conservative in the typical sense of the word. At 60 she remained a liberal skeptic and a compassionate realist with a great sense of irony. But that also meant she could see a downside to being attractive to outsiders, the pitfalls of progress, and the dangers of undervaluing what this place has going for it.

Liz was also one of my post-graduate history teachers. My attraction to the past, and specifically to the stories, people and values of this state, did not emerge in a classroom. No course work involved. My undergrad degree was a Bachelor of Science in mass communication and broadcasting.

My early passions were capturing and interpreting reality in photos, on film and early video and telling stories that engaged and informed. Forty-four years ago, however, when first working as a journalist – covering several southwestern Vermont communities – I also developed an urge to understand the real who, how and why behind what was happening around me. The backstory.

Even if it was just a rough first draft of history, reporting should incorporate as much context and background as possible … on a deadline.

As Ken Burns puts it, history is a table around which we can all sit and have a conversation. I’ve come to believe that we can make better decisions by understanding the past, re- examining, recreating, reliving, and remembering it.

The stories assembled here come from material -- anecdotes, documents, books, interviews – collected over those four decades. In 1976, responding to the official bicentennial celebrations, a group of us first developed a people’s history – Vermont’s Untold History, we called it. Being an editor has also helped. In that role over the years I’ve reviewed and worked with the ideas of hundreds of writers. More recently, I’ve been writing a study of the state that revisits its history, opens some new areas for inquiry, and searches for core values.

Before going any further a small disclosure – I’m not a native Vermonter. When I arrived in Bennington in 1968 this was an important, potentially damaging revelation. I was a flatlander, a Yorker even. But I don’t feel that way anymore, and my son is definitely a Vermonter – though like too many of our young people, he has left (temporarily, we hope) for life in Manhattan.

Fortunately, I am not irony deficient.

When I arrived a period known as the Hoff era was winding down. Phil Hoff was one of Vermont’s breakthrough governors, the first Democrat elected to the office in a century. Phil served through much of the turbulent 1960s. “You have to stand up for things,” he told me in 1998, “and if that results in you being defeated, it’s a risk you take.”

Phil was speaking from experience. After three terms as governor, he was beaten decisively in a 1970 run for the US Senate by incumbent Republican Winston Prouty. Years later he still felt that the main reason for that defeat was his civil rights activism, particularly sponsorship of the Vermont-New York Youth Project, which brought Black teenagers up from New York to work and play with White Vermonters. Others point to the polarized politics of the Nixon era, or a whisper campaign concerning his alleged problem with alcohol.

Phil says that latent racism emerged in reaction to the Youth Project. And his position on racial equality is certainly a hallmark of his progressive contribution.

A brief flashback… In the early 1950s, when Phil arrived from Massachusetts just out of Cornell Law School, he heard that the Black captain of UVM’s football team, who had brought his girlfriend up for a weekend visit, was refused a motel room. Outraged, he joined forces with some local clergy and UVM faculty – at a time, by the way, when such discrimination was commonplace.

Later, a Black Air Force officer was refused the right to buy a home when a real estate agent met vocal, local opposition. As Phil put it, the “positive forces” fought back and launched the state’s first anti-racist coalition. Phil said later: “We would go to the neighborhood with a priest, a minister, and a rabbi. And you know, we won every time.”

In the 60s being a Vermont progressive meant supporting changes in the nature and scope of state government. A keystone achievement was, of course, legislative reappointment, which profoundly altered the balance of political power. Those years also brought a major expansion of the state college system, state takeover of welfare, urban renewal, the first rehab programs at Vermont prisons, and the reluctant acceptance that a regional approach to planning was needed.

Other initiatives didn’t fare so well, or were ahead of their time. Regionalized school districts and fair housing legislation came later. As Joe Sherman put it in Fast Lane on a Dirt Road, “Vermonters seemed willing, at least for a while, to go with the irresistible tug of the American century. They were just climbing on board 60 years late.”

Phil Hoff’s rhetoric was clearly progressive, with a strong emphasis on fairness and equality. During his time outside money and Great Society programs poured in. He also encouraged recreational development and welcomed out-of-state investment in manufacturing. On the other hand, he also felt that, to keep government closer to people, regional solutions should be considered more seriously. He was sensitive to criticism of “uncontrolled” growth and argued that dependence on local tax revenues to support schools was one of the main culprits.

And he pushed for a statewide development plan. “It probably wasn’t very good,” he admitted later, “but no one had ever done it before.”

People like James Burke, elected mayor of Burlington seven times between 1903 and 1933. George Aiken and Ernest Gibson, Republicans who challenged their party’s orthodoxy in the 1930s and 40s. Ralph Flanders, who stood up when it counted during the McCarthy Era. Clarina Nichols, a feminist pioneer who left the state to pursue her dream, and of course Bernie Sanders.

But first, let’s return to the early 19th century and the birth of the first truly alternative political party in US history, a party that had its greatest success in Vermont but also created a constitutional crisis that led to the birth of the Vermont state senate. I’m talking of course about….the Anti-Masons, an early example of populism rooted in a desire for transparency and suspicion of elites.

NEXT: The First Third Party

The journey includes vignettes and impressions on how the Anti-Masons briefly took the state, why feminist Clarina Nichols decided to leave, Burlington’s early progressive mayor James Burke and a 1906 fusion alliance that almost overturned the Proctors, progressive Republicans in the 1940s and Phil Hoff’s 60s breakthrough, the Green Mountain Parkway fight, a Vermont conservative who stood up to McCarthy, and the rise of Bernie Sanders.

MAIN CHARACTERS

William Palmer, Anti-Mason Governor

Thaddeus Stevens, Anti-Mason politician and Republican leader

Clarina Nichols, feminist leader who left to keep fighting

Percival Clement, Railroad tycoon, fusion candidate and GOP Governor

James Burke, progressive Burlington Mayor and Clement ally

James Paddock Taylor, Green Mountain Parkway visionary

George Aiken, Republican Governor & Senator

Ernest Gibson, Jr, liberal Republican Governor who expanded the state’s role

Ralph Flanders, US Senator who saved the country from McCarthy

Phil Hoff, first Democratic Governor in 100 years

Bernie Sanders, socialist who changed Burlington and became a US Senator

Liz was not conservative in the typical sense of the word. At 60 she remained a liberal skeptic and a compassionate realist with a great sense of irony. But that also meant she could see a downside to being attractive to outsiders, the pitfalls of progress, and the dangers of undervaluing what this place has going for it.

Liz was also one of my post-graduate history teachers. My attraction to the past, and specifically to the stories, people and values of this state, did not emerge in a classroom. No course work involved. My undergrad degree was a Bachelor of Science in mass communication and broadcasting.

My early passions were capturing and interpreting reality in photos, on film and early video and telling stories that engaged and informed. Forty-four years ago, however, when first working as a journalist – covering several southwestern Vermont communities – I also developed an urge to understand the real who, how and why behind what was happening around me. The backstory.

Even if it was just a rough first draft of history, reporting should incorporate as much context and background as possible … on a deadline.

As Ken Burns puts it, history is a table around which we can all sit and have a conversation. I’ve come to believe that we can make better decisions by understanding the past, re- examining, recreating, reliving, and remembering it.

The stories assembled here come from material -- anecdotes, documents, books, interviews – collected over those four decades. In 1976, responding to the official bicentennial celebrations, a group of us first developed a people’s history – Vermont’s Untold History, we called it. Being an editor has also helped. In that role over the years I’ve reviewed and worked with the ideas of hundreds of writers. More recently, I’ve been writing a study of the state that revisits its history, opens some new areas for inquiry, and searches for core values.

Before going any further a small disclosure – I’m not a native Vermonter. When I arrived in Bennington in 1968 this was an important, potentially damaging revelation. I was a flatlander, a Yorker even. But I don’t feel that way anymore, and my son is definitely a Vermonter – though like too many of our young people, he has left (temporarily, we hope) for life in Manhattan.

Fortunately, I am not irony deficient.

The Hoff Effect

When I arrived a period known as the Hoff era was winding down. Phil Hoff was one of Vermont’s breakthrough governors, the first Democrat elected to the office in a century. Phil served through much of the turbulent 1960s. “You have to stand up for things,” he told me in 1998, “and if that results in you being defeated, it’s a risk you take.”

Phil was speaking from experience. After three terms as governor, he was beaten decisively in a 1970 run for the US Senate by incumbent Republican Winston Prouty. Years later he still felt that the main reason for that defeat was his civil rights activism, particularly sponsorship of the Vermont-New York Youth Project, which brought Black teenagers up from New York to work and play with White Vermonters. Others point to the polarized politics of the Nixon era, or a whisper campaign concerning his alleged problem with alcohol.

Phil says that latent racism emerged in reaction to the Youth Project. And his position on racial equality is certainly a hallmark of his progressive contribution.

A brief flashback… In the early 1950s, when Phil arrived from Massachusetts just out of Cornell Law School, he heard that the Black captain of UVM’s football team, who had brought his girlfriend up for a weekend visit, was refused a motel room. Outraged, he joined forces with some local clergy and UVM faculty – at a time, by the way, when such discrimination was commonplace.

Later, a Black Air Force officer was refused the right to buy a home when a real estate agent met vocal, local opposition. As Phil put it, the “positive forces” fought back and launched the state’s first anti-racist coalition. Phil said later: “We would go to the neighborhood with a priest, a minister, and a rabbi. And you know, we won every time.”

In the 60s being a Vermont progressive meant supporting changes in the nature and scope of state government. A keystone achievement was, of course, legislative reappointment, which profoundly altered the balance of political power. Those years also brought a major expansion of the state college system, state takeover of welfare, urban renewal, the first rehab programs at Vermont prisons, and the reluctant acceptance that a regional approach to planning was needed.

Other initiatives didn’t fare so well, or were ahead of their time. Regionalized school districts and fair housing legislation came later. As Joe Sherman put it in Fast Lane on a Dirt Road, “Vermonters seemed willing, at least for a while, to go with the irresistible tug of the American century. They were just climbing on board 60 years late.”

Phil Hoff’s rhetoric was clearly progressive, with a strong emphasis on fairness and equality. During his time outside money and Great Society programs poured in. He also encouraged recreational development and welcomed out-of-state investment in manufacturing. On the other hand, he also felt that, to keep government closer to people, regional solutions should be considered more seriously. He was sensitive to criticism of “uncontrolled” growth and argued that dependence on local tax revenues to support schools was one of the main culprits.

And he pushed for a statewide development plan. “It probably wasn’t very good,” he admitted later, “but no one had ever done it before.”

***

That’s one kind of progressive – moderate, expansive in outlook, strong for equality, growth and good government. But the definition has evolved over the years, in Vermont and generally. Tonight I would like to discuss a series of progressive eras -- each with a distinct image, program or approach -- and talk about some of the people who played key roles.People like James Burke, elected mayor of Burlington seven times between 1903 and 1933. George Aiken and Ernest Gibson, Republicans who challenged their party’s orthodoxy in the 1930s and 40s. Ralph Flanders, who stood up when it counted during the McCarthy Era. Clarina Nichols, a feminist pioneer who left the state to pursue her dream, and of course Bernie Sanders.

But first, let’s return to the early 19th century and the birth of the first truly alternative political party in US history, a party that had its greatest success in Vermont but also created a constitutional crisis that led to the birth of the Vermont state senate. I’m talking of course about….the Anti-Masons, an early example of populism rooted in a desire for transparency and suspicion of elites.

NEXT: The First Third Party

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Clarina's Choice: Moving On for Women's Rights

Lest I leave the impression that Vermont has always been fertile territory for free thinkers, consider Clarina Nichols, who ultimately traded Vermont for Kansas to fulfill her dreams.

In 1847, Nichols' articles deploring the lack of property rights for women sparked state legislation granting married women the right to inherit, own and bequeath property. Two years later her efforts led to more reforms; laws allowing women to insure the lives of their husbands, legalizing joint property ownership, and broadening inheritance rights for widows.

But she was frustrated. Until women had the right to vote, Nichols felt they would be basically powerless. She wrote: “We are the best judges…and should hold in our own hands, in our own right, means for acquiring the one and comprehending the other…Women must look to the ballot for self-protection.”

Even as a young girl Nichols understood the importance of a “scientific” education for women. If they received any schooling at all, the main lessons focused on home skills like needlepoint, comportment and etiquette. At her graduation in 1829, she delivered a speech titled “Comparative of a Scientific and an Ornamental Education for Women.”

After briefly teaching she married Justin Carpenter, a Baptist minister, and the family moved to Herkimer in New York. The next decade was spent raising three children and running a seminary for young women. But in 1840 she returned to Vermont – with the children but not Mr. Carpenter – and started writing for the Windham County Democrat. Three years later she divorced. Six days after the divorce was final she married George Nichols, editor and publisher of the Democrat.

When her new husband became ill she took over the editing, and under her direction the paper’s circulation grew from 100 to 1,850. She made it more literary and used its pages to advocate for women’s rights and abolition, as well as against the use of alcohol.

She told an 1851 Women’s Rights Convention held in Worcester, Massachusetts, “It is a fact that our wearing apparel belongs to our husbands and when they choose to pawn or sell our clothing for drink, they can do so.”

Nichols’ suffrage work led to a long-standing friendship with Susan B. Anthony but conflict with Vermont’s legislative establishment. Her first appearance at the Statehouse – the first ever by a woman – outraged many people in the audience. The editor of the Rutland Herald threatened to come to the capital with a man’s suit and dress her in it.

After Nichols testified in favor of women’s right to vote in school district elections, the Education Committee concluded that “women are the proper educators and trainers of the young.” But committee members remained unconvinced on suffrage. Instead of acting on the issue, they recommended that women “entrust the advocacy of their views and interests to a male relative or friend.”

Nichols decided that it was time to try a state where she could be more effective. One of Vermont’s restless spirits was moving on.

She picked Kansas, in part, because a temperate climate might improve her husband’s health. But George Nichols died just a year after the move in 1854. Still, her basic hunch was correct. In Kansas, she was able to win campaigns to insert many rights for women into the constitution, including voting rights in school elections. In 1866 she moved to Washington, DC with her daughter, where she ran the Home for Colored Orphans.

The same year that Nichols left Vermont Lucy Stone, already a leading voice for abolition and suffrage, gave a fiery speech in Randolph. People should withhold their taxes until women had the right to vote, she urged. But it was her appearance that created the real stir during that visit. Focusing on her attire, reporters wondered why attractive young women in the audience were parading around in “unfeminine” bloomers. Stone and other activist women had become admirers of Amelia Bloomer’s trousered dresses, which permitted women to work more freely, especially when carrying things.

Vermont’s leaders resisted giving women the vote right up to the end. When a suffrage bill was passed by the state legislature in 1919, Governor Percival Clement called it unconstitutional and refused to sign. In 1920, when the state was pressured to ratify the 19th amendment, the governor again declined to help, refusing to call a special legislative session.

It became national law anyway. A year later, Edna L. Beard, a former school superintendent, became the first woman elected to the state legislature.

In 1847, Nichols' articles deploring the lack of property rights for women sparked state legislation granting married women the right to inherit, own and bequeath property. Two years later her efforts led to more reforms; laws allowing women to insure the lives of their husbands, legalizing joint property ownership, and broadening inheritance rights for widows.

But she was frustrated. Until women had the right to vote, Nichols felt they would be basically powerless. She wrote: “We are the best judges…and should hold in our own hands, in our own right, means for acquiring the one and comprehending the other…Women must look to the ballot for self-protection.”

Even as a young girl Nichols understood the importance of a “scientific” education for women. If they received any schooling at all, the main lessons focused on home skills like needlepoint, comportment and etiquette. At her graduation in 1829, she delivered a speech titled “Comparative of a Scientific and an Ornamental Education for Women.”

After briefly teaching she married Justin Carpenter, a Baptist minister, and the family moved to Herkimer in New York. The next decade was spent raising three children and running a seminary for young women. But in 1840 she returned to Vermont – with the children but not Mr. Carpenter – and started writing for the Windham County Democrat. Three years later she divorced. Six days after the divorce was final she married George Nichols, editor and publisher of the Democrat.

When her new husband became ill she took over the editing, and under her direction the paper’s circulation grew from 100 to 1,850. She made it more literary and used its pages to advocate for women’s rights and abolition, as well as against the use of alcohol.

She told an 1851 Women’s Rights Convention held in Worcester, Massachusetts, “It is a fact that our wearing apparel belongs to our husbands and when they choose to pawn or sell our clothing for drink, they can do so.”

Nichols’ suffrage work led to a long-standing friendship with Susan B. Anthony but conflict with Vermont’s legislative establishment. Her first appearance at the Statehouse – the first ever by a woman – outraged many people in the audience. The editor of the Rutland Herald threatened to come to the capital with a man’s suit and dress her in it.

After Nichols testified in favor of women’s right to vote in school district elections, the Education Committee concluded that “women are the proper educators and trainers of the young.” But committee members remained unconvinced on suffrage. Instead of acting on the issue, they recommended that women “entrust the advocacy of their views and interests to a male relative or friend.”

Nichols decided that it was time to try a state where she could be more effective. One of Vermont’s restless spirits was moving on.

She picked Kansas, in part, because a temperate climate might improve her husband’s health. But George Nichols died just a year after the move in 1854. Still, her basic hunch was correct. In Kansas, she was able to win campaigns to insert many rights for women into the constitution, including voting rights in school elections. In 1866 she moved to Washington, DC with her daughter, where she ran the Home for Colored Orphans.

The same year that Nichols left Vermont Lucy Stone, already a leading voice for abolition and suffrage, gave a fiery speech in Randolph. People should withhold their taxes until women had the right to vote, she urged. But it was her appearance that created the real stir during that visit. Focusing on her attire, reporters wondered why attractive young women in the audience were parading around in “unfeminine” bloomers. Stone and other activist women had become admirers of Amelia Bloomer’s trousered dresses, which permitted women to work more freely, especially when carrying things.

Vermont’s leaders resisted giving women the vote right up to the end. When a suffrage bill was passed by the state legislature in 1919, Governor Percival Clement called it unconstitutional and refused to sign. In 1920, when the state was pressured to ratify the 19th amendment, the governor again declined to help, refusing to call a special legislative session.

It became national law anyway. A year later, Edna L. Beard, a former school superintendent, became the first woman elected to the state legislature.

Friday, November 13, 2015

Wednesday, June 3, 2015

The Politics of Realignment: Sanders and the Greens

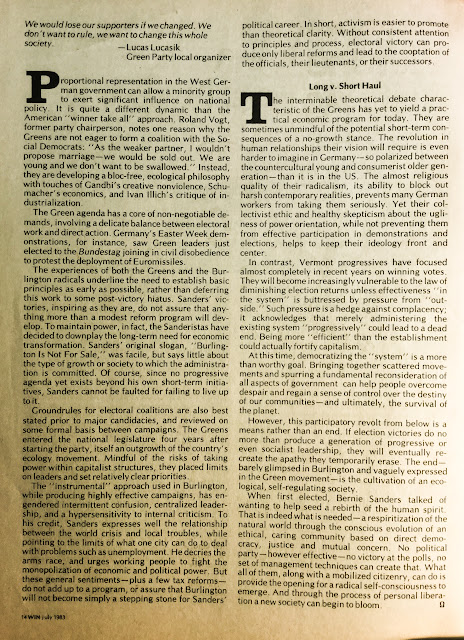

"Warning," shouted the headline of the full-page ad in Burlington's daily newspaper just days before the most watched --and most expensive --elections in city history. Concocted by Bernie Sanders' Republican opponent, the ad listed a series of dire consequences if Burlington's mayor won a second term... (from WIN Magazine, July 1983) A look at the challenges of forging independent alliances and striking a balance between eco-radicalism and effectiveness.

Tuesday, June 2, 2015

Ten Proposals for Preservation & Change

A list of proposals offered by our campaign and defended during the recent Burlington election. Some were also supported by other candidates, or adopted as their ideas. Imitation is a form of flattery and, in this case, one sign of how we influenced the debate. For example, Mayor Weinberger established a group to preserve some BC land, asked for a delay of South End zoning change, and recently claimed there will be no "fast-track" projects. We'll see. Meanwhile, a brief recap of the agenda for preservation and change outlined by the campaign:

- Establish a public interest partnership to preserve BC/Diocese property

- Retain current zoning for the South End Enterprise Zone

- Restore NPA funding at $5,000 each, along with the authority to select staff

- Consider proposals like rent stabilization and a higher minimum wage to address affordability

- Join the federal lawsuit to challenge F-35 basing

- Accelerate marijuana legalization through local research and action

- Begin the process of reforming commission representation to provide more equality and accountability

- Establish standards for public-private partnerships that emphasize responsible growth and protection from gentrification

- Coordinate all stakeholders to assemble capital and retain local ownership of Burlington Telecom

- Tougher negotiations with UVM to house more students on campus, beginning with juniors

Wednesday, May 27, 2015

Lockheed in Vermont: Sanders’ Corporate Conundrum

Progressive

Eclipse – Chapter Ten

Sandia, Citizens United, and Smart Meters: December 2011

EVERYONE WAS TALKING about the one percent, the few with

most of the wealth. The inequality that Bernie Sanders had railed against since

his first campaign was becoming indisputable. Therefore, it wasn’t surprising

that he was one of the first elected officials to back the Occupy Wall Street

movement. Sanders offered practical proposals to address some of its complaints

and praised protesters for “shining a national spotlight on the most powerful,

dangerous and secretive economic and political force in America.”

He was also leading the charge to have Congress consider a

Constitutional Amendment to address a radical Supreme Court ruling. On Jan. 21,

2010, in the Citizens United v. Federal

Election Commission case, the nation’s High Court said that corporations

are “persons” with First Amendment rights and can’t be prevented from spending

unlimited funds on political campaigns.

|

| OWS Protest, October 2011 |

The case had begun in 2008 with a dispute over the right of

a non-profit corporation to air a film critical of Hillary Clinton, and

whether the group, Citizens United, could promote their film with ads featuring

Clinton’s image – an apparent violation of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform

Act, also known as McCain–Feingold. The Supreme Court struck down the

McCain–Feingold provision that prohibited corporations – both for- and non-profit,

as well as unions – from broadcasting “electioneering communications” within

60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary. It did allow for

disclaimer requirements and disclosure by sponsors of advertisements.

The problem went back to the 1970s, when Congress amended

the Federal Election Campaign Act in an attempt to regulate campaign contributions

and spending. After that, in the controversial 1976 Buckley v. Valeo case, the Supreme Court ruled that spending money

to influence elections is constitutionally protected speech and struck down

parts of the law. It also ruled that candidates could give unlimited amounts of

money to their own campaigns.

Prior to Citizens United, however, a century of US

election laws prohibited corporate managers from spending general treasury

funds in federal elections. Instead, they could expend on campaigns through

separate segregated funds, known as corporate political action committees. Shareholders,

officers and managers who wanted a corporation to advance a political agenda

could contribute funds for that purpose. But the Supreme Court’s new ruling said

that corporations had the same First Amendment rights to make independent

expenditures as natural people, and restrictions prohibiting both corporations

and unions from spending their general treasury funds on independent

expenditures violated the First Amendment.

According to Robert Reich, a public policy expert and former

Secretary of Labor, Citizens United would extent corporate control and drive up

the cost of future presidential races. “All this money is drowning out the

voices of average Americans,” he noted. “Most of us don’t have the dough to

break through. Giving First Amendment rights to money and corporations has hobbled

the First Amendment rights of the rest of us.”

The growing influence of corporations made the emerging

relationship between Sandia Laboratories and Bernie Sanders somewhat

perplexing. Sandia was managed by Lockheed Martin for the Department of

Defense, had roots in the Manhattan Project and a history of turning nuclear

research into weapons. Most of its revenue still came from maintaining and

developing defense systems. Beyond that, as Sanders himself had frequently charged,

Lockheed Martin ranked at the top of the heap in corporate misconduct. Between 1995

and 2010 it was charged with 50 violations and paid $577 million in fines and

settlements. Sanders, an opponent of the Iraq war and wasteful military

spending, had been a vocal congressional critic for more

than a decade. It exemplified corporate power and the one percent.

In the mid-1990s, he’d led the charge against $92 billion in

bonuses for Lockheed Martin executives – nearly $31 million of that received from the

Department of Defense as "restructuring costs" – after the corporation laid

off 17,000 workers. He called that “payoffs for layoffs.” In September 1995, after

his amendment to stop the bonuses passed in the US House, Lockheed launched a

campaign to kill the proposal. When the amendment came back to the floor,

Sanders decided that it still contained too much for the military and opposed

it himself.

In 2009, he was still going after Lockheed in the Senate,

calling out its “systemic, illegal, and fraudulent behavior, while receiving

hundreds and hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer money.” By then, however,

he had visited Sandia headquarters and come away eager to have a satellite lab

in Vermont.

Learning

to love Sandia

In January 2010, Sanders led a delegation to Sandia’s New

Mexico lab for a closer look. The group included the CEO of Green Mountain

Power, the state’s leading private utility; the vice president for research at

the University of Vermont; the co-founder of successful alternative energy

companies; and the head of the Vermont Energy Investment Corporation, which runs

Efficiency Vermont.

At the end of the same year, ten days after the

mini-filibuster that jump-started the “draft Bernie” for president campaign,

Mayor Bob Kiss announced the results of his own Lockheed negotiations, begun at

billionaire Richard Branson’s Carbon War Room. It took the form of a “letter of

cooperation” to address climate change by developing local green-energy

solutions.

Lockheed’s proposal to the city focused on “the economic and

strategic challenges posed by our dependence on foreign oil and the potential

destabilizing effects of climate change.” Their partnership would “demonstrate

a model for sustainability that can be replicated across the nation.” Meanwhile,

the Vermont Sandia lab, simultaneously being developed at UVM with Sanders help,

would focus on cyber security and “smart grid” technology. Yet Kiss and

Sanders denied knowing about the partnership being negotiated by the other.

Both Burlington’s Progressive mayor and its famous former mayor-turned-Senator apparently

saw no need to consult. Yet somehow everyone was on the same page.

By 2011, Sanders was also supporting the Pentagon’s proposal

to base Lockheed-built F-35 fight jets at the Burlington International

Airport. Despite his past criticisms of the corporation’s serial misconduct

and excess, he joined with Vermont’s most enthusiastic booster, Senator Patrick

Leahy, signing on to a joint statement of support. If the fighter jet, widely

considered a massive military boondoggle, was going to be built and deployed anyway,

Sanders argued that some of the work ought to done by Vermonters, while Vermont

National Guard jobs should certainly be protected. Noise impacts and

neighborhood dislocation were minimized, while criticism of corporate

exploitation had given way to pork barrel politics and a justification based on

protecting military jobs.

Still, his position hadn’t changed that much. Sandia’s

nuclear associations were never a major obstacle; Sanders had once been

pro-nuclear power, and his criticisms were restrained. His stalwart alliance with

labor had always outweighed his skepticism about military spending. And his

corporate criticism, which focused on fairness and inequality, rarely prevented

him from making an alliance that furthered “bold” initiatives or burnished his record

of leadership.

|

| Pushing the partnership: Sandia's Rich Stulen presents, Powell, Shumlin and Sanders listen. |

When Vermont’s partnership with Sandia was ultimately

announced, Governor Peter Shumlin didn’t merely share the credit for bringing the

Center for Energy Transformation and Innovation to Vermont. He joked that

Sanders was “like a dog with a bone” on the issue. They had agreed to co-host a

press conference on December 12 to outline the initiative, which now included Sandia,

UVM, Green Mountain Power, several Vermont energy businesses and state

government. The ambitious goal, announced the Senator, was to create “a

revolution in the way we are using power.” At this point the “Draft Bernie” for

president campaign was underway and running as a Democrat, most likely in 2016,

was on the table.

For the next three years, Sandia’s new outpost would have up

to $15 million to research energy efficiency, develop renewable and “localized

sources” and, according to Sanders, make Vermont “the first state to have

near-universal smart meter installations.” Shumlin meanwhile announced a Sandia

pledge to invest $3 million a year, along with $1 million each from the

Department of Energy and state coffers.

Several enthusiastic backers – Sandia VP Richard Stulen, GMP’s Mary

Powell, and UVM’s Acting President John Bramley – joined the governor at

Sanders’ Burlington office for the launch. For Sandia, it was “a way to

understand all of the challenges that face all states,” Stulen explained.

Vermont’s size simply made it more possible “to get something done,” especially

since “integration” had already begun with the university, utilities and other

stakeholders.

It didn’t hurt that Vermont’s reputation for energy

innovation had also attracted $69.8 million in US Department of Energy funding

to promote a rapid statewide conversion to smart grid technology. This would be

matched by another $69 million from Vermont utilities. The goal was to “turn

the grid from a one-way into a two-way street,” Stulen announced. Another focus

would be to ensure reliable service. That meant “anticipating any cyber

challenges that may be opened up, or vulnerabilities that may be opened up as

we move to this new future,” he explained. “Sandia is very much in the

forefront of cyber research.”

Sanders’ statement stressed the more provincial point that

although the US had 17 national labs doing “cutting edge research,” none of

them were yet located in New England.

“It occurred to me,” he explained, “that we have the potential to establish

a very strong and positive relationship with Sandia here in the State of

Vermont.” Thus, his intention was to turn the three-year arrangement into “a

long-term presence.” By implication, Lockheed Martin had gone from corporate scofflaw

to valued research partner.

Vermont

as testing ground

“From an environmental, global warming and economic

perspective, it is enormously important that we transform our energy system

away from fossil fuel to energy efficiency and sustainable energy,” Sanders

argued at the launch. “And working with Sandia and their wide areas of

knowledge – some of the best scientists in the country – we hope to take a

state that is already a leader in some of these areas even further.”

For many activists and progressives, it sounded more like

corporate “greenwashing” than a bold step forward.

Shumlin called it “a really exciting development” for the

state. “We have an extraordinary opportunity to show the nation how to use

smart grid, how to use energy efficiency to save money for businesses, and for

consumers. And how to insure that Vermont is the leader in getting off our

addiction to oil.” He noted that when people asked him how Vermont had snagged

so much money for the project, his answer was the partnership the center would represent.

“It’s a huge opportunity and a huge accomplishment.”

On the other hand, there was little dispute that having so

many interactive devices on two-way networks would create new risks. In fact,

Kenneth van Meter, Lockheed’s manager of energy and cyber services, admitted

it, predicting that by 2015 there would be “440 million new hackable points on

the grid. Nobody’s equipped to deal with that today.”

Asked about cyber threats, Stulen acknowledged that “more

portals” certainly did create more potential threats, but countered that “we

think this is a manageable situation. In fact, the benefits far outweigh the

risks.” The main benefit was the potential for lower utilities bills by

monitoring home energy use. But security would also be a focus. “We don’t see

it as an overriding issue right now, but as a national laboratory our job is to

anticipate the future,” he said.

Smart Meters, the basic unit of a smart grid, are digital,

usually wireless utility meters with the ability to collect information and

transmit it to a central location. Supporters claim their widespread use will

improve energy efficiency, service reliability, and the environment. Critics

counter that they also make the power grid more vulnerable to hacking, have

potential radiation-related health effects, and don’t really reduce energy

consumption. They also charge that “time-of-use” pricing penalizes people who

can least afford it, while a centralized grid threatens privacy and gives

corporations more access to private data.

Smart meters have also been linked to fires and other

damage, but aren’t covered by homeowners insurance because the devices haven’t

been industry-approved. Needless to say, such problems and potential side

effects didn’t come up at Sanders’ press conference.

Instead, the Senator explained that “the federal government

has invested $4 billion in smart grid technology, and they want to know that

we’re going to work out some of the problems as other states follow us. So

Vermont, in a sense, becomes a resource for other states to learn how to do it,

how to overcome problems that may arise.” Another way to put that: Vermont

would be a testing ground, Sandia’s smart grid guinea pig.

It was a good example of Sanders’ style and pragmatism,

leveraging Vermont’s assets in a privately negotiated arrangement, a public-private

partnership with PR value and short-term economic benefits – but unknown

long-term consequences. And justifying the high-level deal on the grounds of

leading the nation, a transparent appeal to state chauvinism.

“In many ways, we are a laboratory for the rest of this

country in this area,” Sanders crowed. “With Sandia’s help, I think we are

going to do that job very effectively.” But in another way, it suggested that being

a corporate predator wasn’t always disqualifying, especially when weighed

against the mainstream acclaim and leadership role such a partnership would

confer.

Despite the confident presentation, however, the launch ended

abruptly after a single question was asked about the city’s aborted partnership

with Lockheed Martin. Before a TV reporter could even complete his query Sanders

interrupted and challenged it. Lockheed is not “a parent company” of Sandia, he

objected.

Then, as often the case when fielding unwelcome

questions, he declined to say more – about Lockheed Martin or the climate

change agreement Mayor Kiss had signed, the standards adopted by the City

Council, the mayor’s veto, or Lockheed’s subsequent withdrawal from the deal.

Instead, he turned the question over to Stulen, the man from Sandia, who

offered what he called “some myth-busting.”

It was more like a clarification. All national laboratories

are required to have “an oversight board provided by the private sector,” he

said. “So, Lockheed Martin does provide oversight, but all of the work is done

by Sandia National Laboratories and we’re careful to put firewalls in place

between the laboratory and Lockheed Martin.”

In other words, trust us to respect the appropriate boundaries,

do the right thing, and follow the rules. Moments later, the press conference

was over.

NEXT:

A Tale of Two Caucuses

Wednesday, May 20, 2015

Pragmatic Populism: Making Things Happen

Progressive Eclipse - Chapter Nine

January 1999

WE MET AT the start of a mind-boggling week.

President Bill Clinton was two days from launching a new round of Iraq bombings

– on the eve of his own impeachment. As Vermont’s sole representative in the US

House, Bernie Sanders had already made up his mind about Clinton: yes to

censure, no to removal from office or resignation. But he was equivocating on

the subject of intervention.

A critic of high defense spending who had voted against the

first Gulf war, Sanders nevertheless thought that military action was sometimes

appropriate, in Yugoslavia or to oust a dictator like Saddam Hussein. “I do not

want to see a man like this develop biological or chemical weapons,” he

explained. “So, it’s not an easy situation.”

|

| President Clinton's impeachment photo op; Bernie Sanders stands behind Hillary Clinton |

The real trouble wasn’t militarism. he asserted; it was education

and public opinion. Unlike the broad opposition that emerged to the Vietnam

War, Sanders explained, about “80 percent of the American people” were currently

willing to support just about any decision to use force. “That makes it

difficult for people in Congress to oppose it,” even though “the

tactic often backfires.”

More sobering, he didn’t expect that situation to change in

the near future, “until tens of millions of people say no.” And he didn’t think

most peace activists were on the right track. “Winning credibility is the first

step to building a broad-based movement,” he counseled, and the way to do that

is to take on bread and butter issues. “I don’t think you can just look at the

issue of war and peace,” Sanders said. “People have got to know you are on

their side.”

“I have long been concerned that some ‘progressive

activists’ do not stand up and fight effectively or pay enough attention to the

needs of ordinary Americans,” he explained. “Right now, one of the issues I am

terribly concerned about is what is being proposed for social security, which I

think would be a disaster. It affects senior citizens today. It affects future

generations. How much discussion is there of that issue among activists and

intellectuals, who should understand it? I’ve heard very little.”

Before arriving in Congress, Sanders himself had little idea

of how the legislative branch really operated. The same was true during his

early days as Burlington mayor, when he learned hard lessons about dealing with

an unsympathetic city council and entrenched bureaucracy. Being a congressman

change his perspective; years later, he knew how the game was played. But it

still galled him that “what we read in the textbooks about how a bill becomes a

law just ain’t the case.”

As an example he pointed to conference committees, which are

supposed to iron out legislative differences. “How many people know that when

you have the House and Senate agreeing on a position, the ten people in that

room can junk it completely – even when there is agreement?”

It was the kind of rhetorical question that peppered his

speech, this one conveying an angry belief that the public is kept in the dark

about routine abuses of power and corruption of democratic processes. “I get

outraged at both the television and newspapers about their refusal to educate

people about how the process works,” he complained.

A key lesson of his early years in Congress was that winning

often involved working with people whose stands on other issues you abhorred.

In fact, much of his legislative success came through forging deals with

strange ideological bedfellows. An amendment to bar spending in support of

defense contractor mergers, for example, was pushed through with the aid of

Chris Smith, a prominent opponent of abortion. John Kasich, whose views of

welfare, the minimum wage and foreign policy could hardly be more divergent

from Sanders’, helped him phase out risk insurance for foreign investments. And

a “left-right coalition” led by Sanders helped to derail “fast track”

legislation on international agreements pushed by Bill Clinton.

Now at the mid-point of his US House career, Sanders had

become skeptical about the urge to “moralize and be virtuous and not talk to

anybody.” While acknowledging that it felt odd at times having

ultra-conservatives as political allies, “the job is to pass legislation– and I

say that in a positive sense – so you seize the opportunity to make things

happen."

Still, closer to his heart was another role – provocateur.

“I respect people who are in the political process,” he put it with a smile. He

also obviously enjoyed flushing out political elites. “Issues affecting

billions of people with the world not knowing what’s going on,” he complained.

“I think, as a result of the role I and other have played, there may be more

transparency. But obviously the issue goes beyond that.”

We were getting to the root of his worldview: international

financial groups protecting the interests of speculators and banks, at the

expense of the poor and working people behind a veil of secrecy. Governments

reduced to the status of figureheads under international capitalist management.

Both major political parties kowtowing to big money flaks. Media myopia fueling

public ignorance. And himself, a truth-teller whose message changes history.

His task, Sanders had long ago decided, was to raise

political consciousness and expose the real agendas of the powerful.

Yet when I asked whether he would consider a run for

president he laughed. It would be fun, he admitted, and predicted that “we’d

get a good response.” At that point, however, before his election to the

Senate, the calculation was that staying in Congress gave him more influence

than running an “educational” campaign.

Sanders said he considered it “imperative that people keep

working on what is a very difficult task; that is, creating a third party in

America.” But he had no plans to help develop one, in Vermont or elsewhere. “I

am very much preoccupied and work very hard being Vermont’s congressman,” he

pointed out, deflecting such a responsibility with customary bluntness: “I am

not going to play an active role in building a third party.”

This sounded like a contradiction, but also reflected his

experience and political predicament. He endorsed the idea of building a third

party – in principle. But he had maintained an arms-length relationship with

political parties since his races in the late 1970s. He seemed sincere when

expressing the hope that the Progressive organization he’d helped to build

would expand beyond Burlington – and he sometimes endorsed Progressive

candidates. But he also backed Democrats, and sometimes discouraged

Progressives from running, while generally avoiding involvement in

party-building – especially since that could lead to calls to support

Progressive candidates against Democrats.

Over time Sanders had made peace with the Democratic

leadership. And he had never been embarrassed about playing to win. After all,

he was making history, as he pointed out more than once. If the choice was

between a “virtuous protest” and “popular appeal” he naturally went with the

path to success – as long as it didn’t violate any core beliefs.

Meanwhile, he could justifiably claim that there were “not

very many members of Congress who hold my views. The President does not hold my

views. The corporate media does not hold my views. That is the reality I have

to deal with every single day.” His job, as he had defined it, was to

understand the constraints of politics and “do the best you can with the powers

you have. You don’t just stand on a street corner giving a speech.”

The remark sounded almost ironic. After all, giving a speech

– pretty much the same one – is what Sanders does best. Over the years it had

already taken him from third party obscurity to the most private club in the

world. And after the 2008 financial meltdown and election of Barack Obama, it

was only a matter of time until his pungent mix of middle-class outrage and

“flexible” populism went from C-SPAN to prime time.

NEXT: The

Lockheed Conundrum

Thursday, May 14, 2015

Bernie's Paper Trail: The Burlington Years (1981-1990)

Progressive Eclipse - Chapter Eight

UPON LEAVING THE mayor’s office after four terms, Bernie Sanders donated more than 50 boxes of official papers and files to the University of Vermont library. The index created by UVM's Special Collections listed around 1,400 separate files covering March 1981 to November 1988. According to Sanders aide George Thabault, much correspondence during the first few years had been lost. But what remained ran from Abenaki to Zoning. About 10 boxes covered areas like administrative meetings, speeches and statements, commissions, selected departments and people, proclamations and controversial topics.

To a supporter who thought, in 1988, that Sanders was a socialist candidate for Congress, he explained candidly, “Socialist is the political and economic philosophy I hold, not a party I run under.” And when two Californians asked in a letter, “What does Socialism really mean in the United States at the current state of conditions and confusion that exists at all levels?” he offered this characteristic reply:

|

| Reading poetry at Maverick Bookstore, 1986 |

“That’s an excellent question which I really don’t have time to answer now. I will simply say that in Burlington we have a three-party system – Progressive, Republicans and Democrats, and that I think we are doing many good things for working people, poor people and elderly people in our community.”

People often urged him to run for one thing or another. They also offered advice, warnings and pats on the back. Author Gerard Colby, for example, noted in a November 1983 letter that interstate banking would hurt efforts to stop condominium development on the waterfront by giving entrepreneurs and developers “a valuable and powerful ally beyond Vermont’s borders.” Three years later, that became a hot statewide issue.

Around the same time, Montpelier attorney Richard Rubin expressed his concern that the city might be duped in dealings with developers of the waterfront. “I thought I would point out to you that the term ‘profit’ has little meaning in large-scale real estate developments,” he wrote. “These projects can operate as substantial balance-sheet losses but still be quite lucrative to the investors. I am sure there are good accountants who can explain this to you.”

By Spring 1984, Sanders had statewide visibility and growing political power. With George Thabault’s victory in solidly Democratic Ward 5, the Progressives had gained a sixth seat on the City Council. Sanders considered briefly, but then rejected the idea of a run for governor that year. Many people offered opinions on what he should do. Among them was Democrat Peter Welch, himself a potential statewide candidate. Welch wrote, “Congratulations on your recent victories. Perhaps your opponents have come to the reluctant conclusion that the politics of obstruction doesn’t work. While I understand your decision, many have looked forward to your campaign. Perhaps another day.”

In 1990, Sanders did the convincing. He persuaded Welch to run for governor instead of the US House of Representatives, while he made his successful bid for Congress. Welch lost. But the two remained political allies, and when Sanders became a US Senator in 2006 Welch replaced him in the House.

Occasionally Sanders offered advice to presidents. To Ronald Reagan, on the occasion of declaring October 24-31, 1981 Disarmament Week in Burlington, he wrote:

“I urge you, in the strongest possible way, to stop doing ‘business as usual.’ International conflicts can no longer be solved by war. It has no worked in the past, and it may well destroy the world in the future.”

Several years later, he made a proposal to former President Carter: that Carter visit Nicaragua and help build some housing. “Your presence there,” he urged in August 1985, “would send a powerful message to the citizens of the United States, challenging them by the model of your own efforts to provide material aid to help the people of Nicaragua in constructive ways."

Despite his stated desire to change military and foreign policies, however, there wasn’t much in his papers about local support for these goals. His coolness to economic conversion of Burlington’s armaments plant was evidenced by the absence of any file on the subject. In 1987, he did note to activist Robin Lloyd that opposition to any peace initiatives that "cost jobs" would be enormous.

Still, he did add, “I believe that a rational conversion policy will not only result in more employment opportunities for Americans but in a radical improvement in the quality of life in our country.” It was more support for changing basic military spending priorities than he ever gave in public.

On the Rise

By 1983 the Sanders administration and local progressive movement were in high gear. The minutes of the April 6 administrative meeting show a broad and systematic approach. Personnel Director Peter Clavelle and Treasurer Jonathan Leopold were at the center of things. Clavelle ended up succeeding Sanders as mayor. Leopold, although leaving city government after a succession rivalry with Clavelle, returned as the City’s Chief Financial and Operating Officer under Clavelle’s successor Bob Kiss. In 1983, they were pushing plans to expand health insurance for city employees, streamline Council meetings, bring more women into the Police Department, and push through interim zoning.

An April memo listed more than 40 actual and proposed projects, including a rental housing clearinghouse, alternative school, emergency shelter, office of arts and culture, international work camp, taxi subsidies, park improvements, youth center and self-defense classes. Each month the list got longer.

Among Sanders’ frustrations about Burlington’s form of government, commissions were at the top of the list. Commissioners, a majority of them aligned with the Democrats and Republicans, controlled most city departments. Attempts to unify and streamline were resisted until Clavelle, a decade later, succeeded in pushing through charter revisions favoring a strong chief executive. Prior to Sanders’ election the vast majority of commission appointments were made with only one candidate in the running. In 1980, only two out of 25 appointments were contested. Two years later, all but two involved competition.

In a March 1983 letter to the City Council Sanders focuses on one area of concern. “Of the 103 citizens currently serving on Burlington’s commissions,” he reminded them, “only 21 are women. Clearly, the City of Burlington wants to address this serious inequality of representation.” But he wanted more than that, changes in the city charter and shorter terms for commissioners. The current structure, he said, relies on Council members “for handling many routine administrative matters more properly the responsibility of an executive. The Mayor competes with a variety of independent boards, commissioners, committees, and individuals.”

|

| Representation on commissions remains a problem |

When the Council asked for a clarification, the city attorney wrote back, “Some commissions are subject to orders issued by the City Council while other are not.” In fact, at least eight commissions, including traffic, police, planning, parks and recreation, light and the library, were not subject to the council’s orders in areas delegated to them by the charter. Determined to unify administration, Sanders and his staff turned to departmental mergers, starting with the Department of Public Works. Others were considered during the 1980s.