Bennington in Changing Times

Opening a Senate investigation of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution in March 1968, Sen. J. William Fulbright described what was taking place across the country as a “spiritual rebellion” of the young against a betrayal of national values. The war in Vietnam was coming home.

Opening a Senate investigation of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution in March 1968, Sen. J. William Fulbright described what was taking place across the country as a “spiritual rebellion” of the young against a betrayal of national values. The war in Vietnam was coming home.

In Bennington a cultural storm was brewing as newcomers arrived in Vermont during the late 1960s. At its center were the schools. Fifty years later, photos and ideas from this video essay helped to inspire an exhibit in 2019 (6/28-11/3) at the Bennington Museum, Fields of Change: 1960s Vermont. The sound track includes music by John Cage, Spirit, Donovan, Bob Dylan and Eric Anderson; guitar and vocals by Dave Putter; photos, narration, piano solos and editing by Greg Guma. With thanks to Jamie Franklin.

Review: Lasting Impact

“Although the epicenters of the counterculture movement were located in and around Brattleboro and Plainfield and throughout Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, the Bennington area boasted its own artists, artisans, photographers, clothing designers and political activists whose work brought the larger story to the local arena, sometimes resulting in opposition.”

Narration

In March 1968, Sen. J. William Fulbright described what was taking place across the country as a “spiritual rebellion” of the young against a betrayal of national values. Over half a million troops had been mobilized to fight in Vietnam. The operative logic was that it might be necessary to destroy the country in order to save it.

Then a shot rang out in Memphis and ended the life of Martin Luther King Jr. Demonstrations erupted in 125 cities. More than 20,000 arrests. The mobilization of federal troops and the National Guard. Two months later, Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles, just after winning the California primary.

By Summer, there had been over 220 major demonstrations on campuses across the country.

By Summer, there had been over 220 major demonstrations on campuses across the country.

By then I had moved to Vermont. And I wasn’t the only one. Thousands of us came. I was with a group of young idealists who wanted to distribute and distribute films. The first step was to create film societies across the Northeast.

The name of our dream was the American Film Academy.

“Strange country up here; New Hampshire and Vermont appear to be the East's psychic answer to Colorado and New Mexico – big lonely hills laced with back roads and old houses where people live almost aggressively by themselves.” — Hunter Thompson

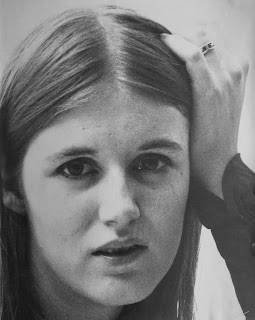

That’s Kitty when she was around 20. We’d fallen in love and gotten married. She was from Shaftsbury, but we found a place in the Village of Bennington. And kindred spirits.

Then a cooler place on Depot Street, with a health food store downstairs. We called it the Gingerbread House. But that was later...

In September, some young Republicans hired us to produce a multi-media light show for a state GOP meeting at the Paradise motel. It was a strange idea — but the Academy was in trouble and we were desperate. The reaction was less than enthusiastic.

Afterward, Liz Dwyer wrote a scathing article for the Bennington Banner. It was so upsetting that we had to reply in a letter to the editor. We saw ourselves as creative entrepreneurs. But some people saw us as part of an unwelcome invasion:

“As AFA employees, we are upset most about the glib manner in which our organization is maligned by people who do not understand our work and are afraid to inquire about it.”

“We are teachers, students, and artists....We do not circulate underground or low-life films... In fact, we are now supplying the films for the YMCA film program.”

By then, two of us had taken temporary teaching jobs at The Prospect School, a progressive elementary school in North Bennington. Its aim was to deepen each child’s experience of the world through individualized instruction and working with all kinds of materials. The kids were free to move around, talk with others, and pursue their own projects and ideas.

It was great work. But soon I took a very different job, reporter and photographer for the Bennington Banner ... and found myself working with Liz Dwyer, the editor who had panned our light show. We became great friends.

On my third day the editor, Tyler Resch, took me to a school board meeting, drew a diagram of people around the table. And left. It was sink or swim. And a political storm was brewing. A new high school had been built. But it was also at the center of Bennington’s cultural divide. Its alma mater, “The Impossible Dream,” turned out to prophecy. An idealistic plan for progressive local education was about to be derailed.

The school superintendent resigned and a dispute had developed over who would replace him. The elementary school board wanted the Assistant Superintendent. The supervisory union wasn’t so sure.

It looked like a minor dispute. But it was really part of a bitter struggle, a local culture war, and the stakes were the future of education and community life.

A Golden Age

In the 1930s Martha Graham was instrumental in making Bennington College the epicenter of the modern dance world. The Bennington School for Dance, precursor of the American Dance Festival, was an innovative laboratory where pioneers experimented, trained students, and created early works that defined modern dance.

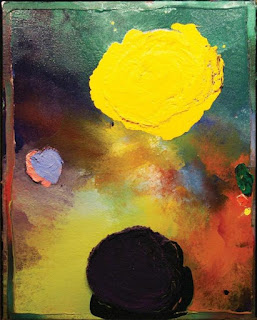

A generation later the area became a nexus for modern art. As the story goes, it began with art critic Clement Greenberg and painter Helen Frankenthaler. They were soon joined by Paul Feeley and other painters who helped connect the emerging avant-garde movement based at the college with the New York art scene.

By the 1960s the community was hosting a veritable artist colony — although many folks did their best to ignore it. An article in Vogue even updated Vermont history, calling painters like Anthony Caro, Kenneth Noland, Vincent Longo and Jules Olitski the new Green Mountain Boys.

The original Green Mountain Boys were a revolutionary era militia led by Ethan Allen, who met at the Catamount Tavern in Old Bennington. It burned down in 1871.

A century later Greenberg’s idea was that art should be disciplined, but without sacrificing vitality. The concept combined distance with enjoyment and freedom. Bennington seemed perfect ... not far from New York and Boston, but sufficiently removed. An ideal place to play out an unusual artistic vision.

But the golden age was over by the time I arrived. And a conservative political storm was brewing. At its center was the high school.

Impossible Dreams

Mt. Anthony Union High School was thriving ... a new campus, engaged students, creative faculty. Even professional level productions of big musicals like West Side Story, The Fantasticks, and My Fair Lady.

It wasn’t all about the arts. There were also innovative vocational programs and volunteer projects like DUO, a state idea. The name stood for “do unto others” and it let high school students spend half of a School year on a project that responded to a real community need.

But what made Mt Anthony different was a creative spirit, and the dynamic head of the music Department, Jack Carton.

But a power struggle was brewing between two tribes. And then the state Commissioner of Education stepped in.

To break the superintendent stalemate he unilaterally merged Bennington’s Supervisory Union with another board and appointed its superintendent to head the new “super district.” George Sleeman could keep his job. But his rise had been blocked. His allies were stunned and his brother would not forget. The struggle between modernists and traditionalists would continue for years.

After that the first public flashpoint was a high school musical, and the spark was the poster. The poster was banned and on opening night the house was half-filled. It almost felt like a boycott. I didn’t realize it at first, but a moral majority culture war had just begun.

Yet protests were also growing — against the Vietnam War, and the culture war at home.

Fifty years later it all became an exhibit at the Bennington Museum.

Fifty years later it all became an exhibit at the Bennington Museum.

Greg Guma, a journalist, magazine editor, community organizer, and the author of several books including The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution, supplied numerous photographs and much of the background information for the exhibition. Like many young, progressive activists and hippies, Guma moved to Vermont after graduating from college. “It was 1968 and I was fairly traumatized by what was going on during my final semester,” he said. “The war, the election of Nixon, the protests, the assassinations. Like a lot of people, I wanted to flee the violence and try to find better values in a less complicated environment.”

Guma got a job as a reporter and photographer at The Bennington Banner where he chronicled many of the historic changes taking place in the state. “I was one of only two reporters, so I was exposed to many aspects of society,” he said. “I watched the culture war unfold.” — Stratton Magazine, 8/30/2019